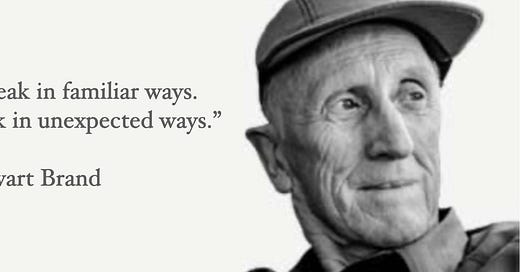

A Stewart Brand Playlist

Here's a curated list of what to read/watch/listen to from Stewart's remarkable career so far.

(From Part Two of our conversation, On Silver Ghosts and AK47s.)

One of the things I’m most looking forward to about the Adjacent Possible newsletter is the regular series of email-based conversations I’m going to be hosting with some of the smartest people I know. (Upcoming guests include folks like Adam Grant, Rebecca Skloot, Ezra Klein, and many more.) The full conversations are only available to paid subscribers, so I encourage those of you who haven’t signed up to do so now. (Think about it: all these brilliant people in your inbox each month—plus original new essays from me—all for the cost of one single overpriced coffee!) But it occurred to me as I was emailing with Stewart Brand this past week that I could also use this as an opportunity to write a little tribute to each of my guests, basically a playlist of suggested links that I think captures the full range of their work, and share that tribute with the entire email list.

Now, it turns out that with Stewart Brand, creating a playlist that does justice to his career is a near-impossible task, because he has been involved in so many different social and technological enterprises over the years. I remember having lunch with Stewart shortly after we moved to California about ten years ago, and saying to him that one of the things that had always struck me about the Bay Area is how central it has been over the past half-century in generating new transformative ideas that end up having a global impact, despite being the twelfth-largest metro area in the US by population size. I mentioned the rise of the counter-culture in the 60s, the environmental movement in the 70s, the PC revolution and the rise of online networks—and then I looked across the table and realized that Stewart had played an important role in all of them. “Maybe it’s not the Bay Area,” I laughed. “Maybe it’s just you, Stewart!”

So with the caveat that this is just a small representative sample of Stewart’s career, here are a few highlights that influenced me over the years:

How Buildings Learn: What Happens To Them After They’re Built. One of my all-time favorites, both in terms of the underlying argument and the physical design of the book itself. On the surface, it’s a book about architecture, but at its core it’s about how systems and structures evolve over time, and how we can steer that process so that they improve as they age. (Very much related to Stewart’s new project, Maintenance: Of Everything.)

SpaceWar: Fanatic Life and Symbolic Death Among the Computer Bums. Did you know that we have the term “personal computer” (and the acronym PC) because Stewart wrote an 8,000 word Rolling Stone piece about the world’s first videogame back in the early 1970s? (I wrote about SpaceWar in my book Wonderland, and interviewed him for a fun podcast episode we did on the subject, “32 Dots Per Spaceship.”)

The Clock of the Long Now: Time And Responsibility. A great introduction to one of the most important of Stewart’s projects from the past decade or so: The Long Now Foundation (which Stewart co-founded) and its plans to build a clock that will keep time for ten thousand years. I used a quote from it as a chapter epigraph in my book Farsighted: “What happens fast is an illusion, what happens slowly is reality. The job of the long view is to penetrate illusion.”

The SALT Talks. Another part of Long Now Foundation, these “Seminars on Long-term Thinking” feature a wide range of guests, many of them interviewed at the end of the talk by Stewart.

The Whole Earth Catalog. I was born too late to be influenced by this directly, but you can see the tremendous impact it had on an earlier generation by reading the last section of Steve Jobs’ legendary Stanford commencement address. “Stay Hungry. Stay Foolish.”

The Dawn of De-extinction. Are You Ready? Stewart’s TED Talk making the case for his most recent—and perhaps most controversial—project: using genetic engineering to revive extinct species. (I’ll be talking to his partner Ryan Phelan about this initiative in a future newsletter.)

We Are As Gods. There’s a wonderful documentary about Stewart’s career (directed, as it happens, by two of the directors of my PBS series Extra Life) that has not yet been released. (I’ll be sure to update this email list with news once it’s available for streaming somewhere.) But as a teaser, this is a fascinating conversation between Stewart and Long Now co-founder Brian Eno. (Look out as well for a major biography of Stewart written by John Markoff, coming out next year.)

Finally, I thought I’d share a bit from our conversation here at Adjacent Possible, previewing some of the ideas in his next book, Maintenance: Of Everything. (One last reminder to sign up for an amazingly inexpensive subscription to read the whole thing. Or a slightly more expensive one if you’d like a personalized signed copy of my new books.) And below, a bonus image that Stewart sent me of a young Lieutenant Brand (on the left) directing a company of trainees into a chest-deep swamp in Fort Dix, New Jersey, 1962.

Cheap, clunky, and maintainable wins time after time…. Now we come to assault rifles. I have a dog in this fight because I was a professional rifleman for two years of active duty as an Infantry Officer in the early ‘60s. If I had stayed in the Army I might well have wound up in Vietnam as a Company Commander of a line unit—totally responsible for the safety of my 200 men, mostly draftees.

In the earliest years of the war the North Vietnamese outgunned US forces on the ground. They had AK47s—a cheap, highly effective "assault rifle"—which means a gun that can shift from semi-automatic (bang bang bang) to fully automatic (braaaaaaapp). The US responded by fielding a brand new, highly sophisticated, cutting edge assault rifle called the M16. It was extremely accurate, even out to 500 meters. It was light, with a distinctive carrying handle on top. The butt was in line with the barrel, so it did not “climb” when fired on full auto. It was ergonomically brilliant--perfectly balanced, smooth operating, with every control in easy, intuitive reach.

Old systems break in familiar ways. New systems break in unexpected ways.

In the jungles of Vietnam the M16 had a flaw. The definitive fatal flaw. It jammed in combat, leaving the rifleman exposed and helpless in a firefight. One Marine reported: "We left with 72 men in our platoon and came back with 19, Believe it or not, you know what killed most of us? Our own rifle. Practically every one of our dead was found with his M16 torn down next to him where he had been trying to fix it.”

Steven