Designing a Workflow For Thinking

We’re living in a golden age of tools for thought. But with so many options, it’s important to carve out time every year or two for a “creative inventory” of how you discover and organize your ideas.

[TLDR summary: I’m going to be publishing a series of essays about building the most effective creative workflow, including annotated lists of some of the best tools and techniques out there. This series will only be available to paying subscribers, so if you’re interested, I encourage you to sign up for the paid version now.]

At some point in the fall of 1987, during my sophomore year of college, Apple released a strange but—to me at least—intoxicating new application called Hypercard. There’s an old joke about the Velvet Underground that I think is attributed to Brian Eno: only thirty thousand people bought the first VU album, but everyone who bought it went on to form their own band. Hypercard was kind of like the Velvet Underground of interface design in that period. It never became a mainstream platform, but I suspect a lot of us who got obsessed with it ended up doing interesting new things with software and online networks over the subsequent years.

Hypercard, as the name suggests, revolved around the metaphor of a stack of cards; instead of “documents,” in the Hypercard world you created stacks. Crucially, specific information on each card could be linked to information on other cards. I think it’s correct to say that Hypercard was the first commercial product of any scale to introduce the idea of navigating through user-created links—an architecture that would come to dominate the world a decade later when the Web finally became our central shared information space.

In my case, I immediately dove into creating a Hypercard stack that would allow me to capture notes for all of my classes. I learned the simple but elegant programming language Hypertalk and immersed myself in building a stack that I called “Curriculum.” I quickly found myself in the ironic situation of spending so much time building a tool to help with my schoolwork that I stopped actually doing my schoolwork.

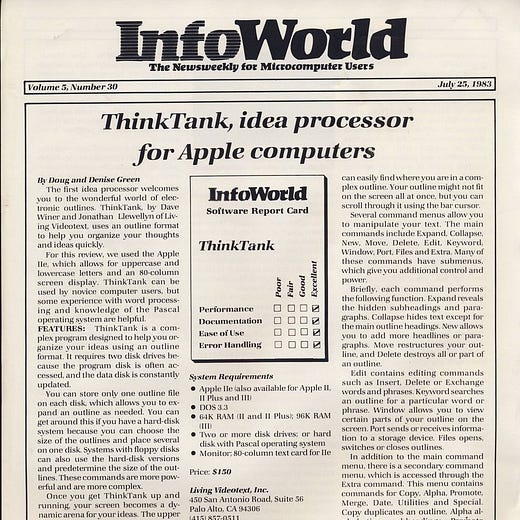

I don’t think I ever got Curriculum to a place where it really lived up to my aspirations—but it did give me a tantalizing hint of something that I’ve been chasing ever since, what Howard Rheingold called in his visionary book written around that same time “tools for thought”: using the computer not just to compose your thoughts in the form of written documents, but instead using it as a tool for having more interesting thoughts in the first place. On Twitter a few days ago, Dave Winer shared this review from 1983 of his early application ThinkTank, which Infoworld dubbed “an idea processor.” That’s maybe too close to “word processor,” but it gets at the core concept: software that helps you generate ideas, remix them into new combinations. Software that serves as a seedbed for your ideas.

If you’ve followed some of my writing over the years, you know this obsession has continued, more or less unabated. I still get emails every few weeks about a piece I wrote for the New York Times in 2004 about my use of the idea database Devonthink; a post I put up on Medium years ago about how I capture and revisit early stage hunches is one of the most-read pieces I’ve written there. In 2010 I published a whole book ruminating on these themes: Where Good Ideas Come From.

There was, I suppose, a more straightforward how-to book lurking inside Good Ideas, but for whatever reason I have a hard time writing books in a purely prescriptive mode that just lays out the tools and habits that can help you achieve a goal like having more generative ideas. But the truth is I have been collecting strategies for what I suppose we could call “idea hacking” for decades now, and there are more software applications out there to help you cultivate new ideas—all those descendants of Hypercard—than ever before. (Some of them, like Roam and Readwise, were specifically inspired by some of my writing on the subject, which has been very gratifying to see.) As it happened, a couple of months ago the folks at the e-course platform “Five Things I’ve Learned” asked me to teach an online class about the creative process, which got me to organize a lot of those strategies and tools into a more coherent presentation. And then it occurred to me that Adjacent Possible would be fantastic venue to share all that information I’d been collecting over the years.

One meta-strategy that I’ve developed over the years is what I’ve come to call taking a “creative inventory.” In my line of work as a writer, there’s a near endless stream of new applications coming out that touch different stages in my workflow: e-book readers, notetaking apps, tools for managing PDFs, word processors, bibliographic databases. The problem is that it’s very tricky to switch horses midstream with these kinds of tools, which means you have a natural tendency to get locked into a particular configuration, potentially missing out on better approaches. So I’ve started a routine where every few years, I block out a couple of days to sit down and review all my idea tools—and other rituals of how I structure my creative thinking— to see if there's something that can be improved upon. Maybe it's some new note-taking software that's just been released; maybe it's something in my daily routine that needs to be re-organized. And from that process I deliberately design a creative workflow that becomes my default standard for the next few years.

So what I’m going to do here at Adjacent Possible is share a series of documents that are all structured around the key questions you should ask yourself in designing that creative workflow. Questions like: how do you capture your own hunches? How do you capture ideas from other people? How do your ideas evolve over time? How do you engineer surprise and serendipitous discovery into your routine? (My hope is that it will be useful to everyone, no matter what your profession happens to be—I won’t just focus on book-related tools.) For each question I’m going to write a short essay supplemented by an annotated list of the tools and strategies that I’ve found interesting; I’ll update the documents as new applications emerge, or perhaps as members of the Adjacent Possible community share their own ideas. These posts will only be available to paying subscribers, so if this seems of interest, I’d encourage you to sign up for the paid tier. And if you’re already paying—thanks for your support, and here are the first installments in the series:

How do you capture your hunches? Big ideas invariably come into the world as fragments, hints of possibility. How do you make sure you don’t lose track of them?

Capturing and Colliding: How do you retain and remix ideas from other people’s minds? A 300-year-old productivity hack might be the key.

Seven Types of Serendipity: From untidy desks to post-it notes to the brewery next door—so much of the creative process is about being open to happy accidents. But how do you make them more likely to happen?

The Serendipity Engine: In which I ask a simple question: “How do you surprise yourself?”

is there a list of all of the workflow for thinking posts?

ever heard of Zettelkasten?