Getting To Scale

With Omicron rising, and new antivirals on the way, we need to remind ourselves that inventing life-saving treatments is only half the solution.

[You’re reading a post from my newsletter, Adjacent Possible. Between now and January 1, I’m going to contribute 20% of new subscription revenue to the SEVA Foundation. You’ll have full access to some of the exciting projects I’ve got in the works for Adjacent Possible in 2022—and you’ll be giving the gift of sight…]

I’m writing this from New York City, currently one of the global epicenters of the Omicron wave. I was here in March of 2020 as well, and it’s hard not to be reminded of those terrifying early weeks of the pandemic. There’s always something striking when you detect broad global patterns—like the spread of a new viral variant—in your quotidian daily interaction with friends and colleagues. I would say anecdotally that we have heard of more COVID-positive cases or exposures in our extended social circle in the past week than we did at the height of the first wave in 2020. (Only mild symptoms so far, thankfully.) The severity of an Omicron infection is still a matter of debate, but the evidence is clear about one thing: this variant is shockingly good at getting itself transmitted from host to host.

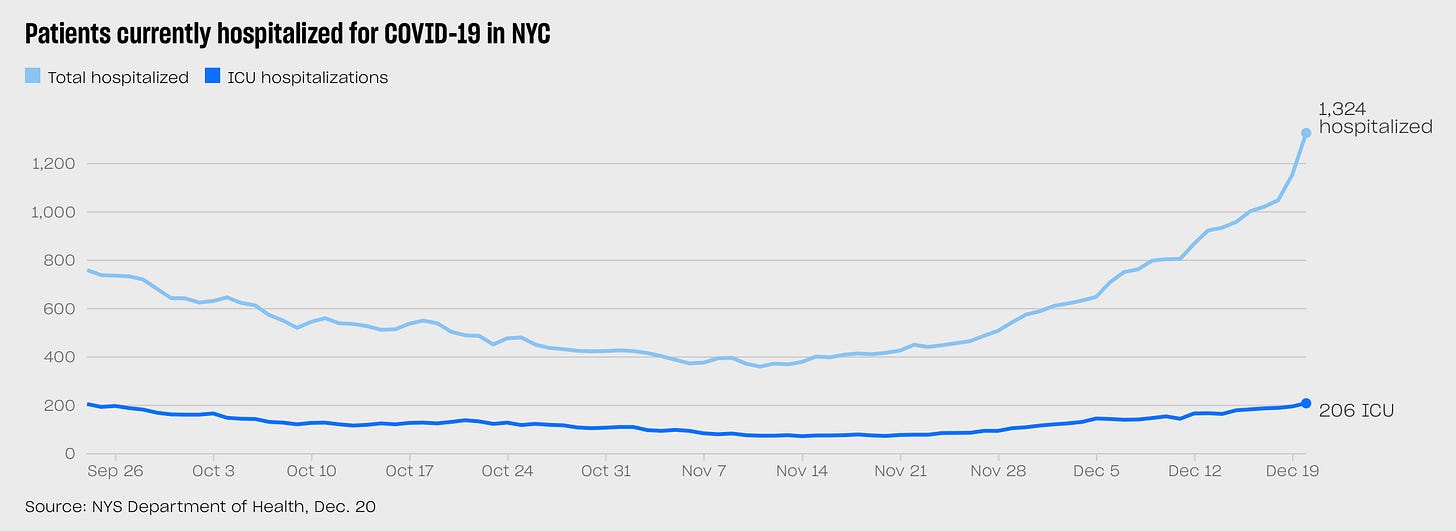

It’s hard to avoid a sense of dread at points like this, in these uneasy days as Farr’s curve starts to ascend in the daily updates, given what we lived through almost two years ago. But of course the world is a very different place now. The best way to visualize this difference is to look at these two charts, each representing the same data — NYC COVID hospitalizations/ICU patients over time — at different scales. Here’s the story of the past 90 days:

Looks alarming—a marked spike in hospitalizations, and ICUs have doubled in the past month. But then look at the same data, visualized over the past two years.

Seen through that lens, the picture is much less unsettling. The upward slope up hospitalizations is almost invisible next to last winter’s wave and the catastrophe of March-April 2020. Now, we are still early in the Omicron cycle, and while there is evidence from South Africa (and perhaps Europe) that Omicron waves tend to crest faster than previous variants, it’s possible that we will see that hospitalizations line continue to climb, ultimately reaching the terrifying heights of earlier waves. But the more plausible scenario is that our T-cells—educated by the vaccines and previous infections—will flatten the curve well before then. What now seems likely—both encouraging and a little depressing at the same time—is that the remaining months of the pandemic will be a succession of these waves, each cresting a little lower than the one before, as immunity (and disease-reducing therapeutics) build up over time, like ripples in a pond slowly returning to equilibrium.

A lot of what I’ve written about the pandemic has focused on the things that we have managed to get right, compared to past outbreaks: the speed with which we identified and sequenced the genome of the virus, the miraculous development of safe and effective MRNA vaccines, the fact that billions of people around the planet made profound adjustments in behavior to flatten the curve. But the rise of Omicron and the imminent FDA approval of the Pfizer antiviral Paxlovid are, in slightly different ways, reminders of something that we should get much better at—namely, the hard logistical and operations work of scaling. We have miraculous vaccines, but the longer it takes us to vaccinate the entire planet, the more opportunities there will be for new variants to emerge. And while Paxlovid looks to be the most significant new advance in the fight against COVID since the vaccines, its production ramp is not going to be fast enough to have any real impact on the Omicron wave. As Matt Yglesias wrote a few weeks ago: “Pfizer says it’ll have about 180,000 packs of Pavloxid by the end of 2021 and then a very rapid ramp up to 21 million in the first half of next year. Those are large numbers, but they are not that large relative to a world population of seven billion or even the 630 million people worldwide who are over 65.”

In last week’s post about serendipitous discovery, I wrote a little about the classic story of Alexander Fleming, accidentally discovering penicillin after leaving a petri dish exposed on his desk during a two-week vacation. I briefly touched on the Fleming story in the book version of Extra Life, and my co-host David Olusoga did a wonderful recreation of it in the TV version. But in both the book and TV show, we emphasized a completely different part of the penicillin story, one that generally gets far less coverage than Fleming’s Eureka moment at the workbench: the extraordinary multinational and multidisciplinary effort to scale production of penicillin in time to get it to soldiers on the frontlines of WWII.

I’ll spare you the details of the story, but suffice to say that it was a far more complex and heroic task than simply stumbling across a curious mold in a petri dish. It involved creating crazy, jury-rigged production systems to test the drug on a single subject; a daring flight across the Atlantic with most of the world’s supply of penicillin in a single briefcase; squads of soldiers dispatched around the world to find other molds that might reproduce more efficiently; a team of agronomists in Illinois who were experts at growing mold in corn steep liquor; and Pfizer’s mass production facilities in Brooklyn. All leading up to one extraordinary result: In 1941, there wasn’t enough penicillin in the world to keep a single human suffering from a bacterial infection alive; and yet just three years later, when Allied soldiers landed on the Normandy beaches on D-Day, they were carrying penicillin packets as part of their standard gear.

It’s an amazing story, and one of the things that struck me researching it is how strange it is that the Fleming narrative is vastly more familiar to most people. And I think that’s because we romanticize—and thus invest in—discovery, and tend to ignore—and thus underfund—scaling. I thought it was striking that Operation Warp Speed—which did a superb job at developing effective vaccines, and a terrible job of actually getting them to people—was originally dubbed MP2, shorthand for Manhattan Project 2.0. According to Politico, then HHS Secretary Alex Azar rallied the troops by saying, “If we can develop an atomic bomb in 2.5 years and put a man on the moon in seven years, we can do this this year, in 2020.” As is so often the case, when we reach for examples of heroic scientific achievement, we turn to the familiar legends of military breakthroughs or space travel, and not the far more relevant example of actually making a drug that saved millions of lives. If they’d code-named the vaccine crunch P2, after the penicillin project, it might well have reminded them that creating a life-saving medical innovation is only half the job; you need to get it into people's arms or mouths on the scale of millions for it to make a difference.

So to my mind, one of the lessons of this pandemic is that we need as much innovation in the approval/production/distribution side of the equation as we do in the lab science that conjures up mRNA vaccines or antivirals like Pavloxid. There are many potential ways of doing this, from challenge trials during the early days of development, to a more aggressive use of the Defense Production Act, to investing in excess production capacity that can be switched on for future crises—to other ideas that no one has thought of yet. And if we’re going to have role models for what we’re trying to do, much better to lean on stories where we mass produced millions of drugs, instead of making a handful of bombs or sending three guys to the moon.

Steven

A reminder: between now and January 1, I’m going to contribute 20% of new subscription revenue to the SEVA Foundation. You’ll have full access to some of the exciting projects I’ve got in the works for Adjacent Possible in 2022—and you’ll be giving the gift of sight…