Magic Cards and Knowledge Bottles

Can AI give us an enhanced version of the "digital librarians" first envisioned almost a half century ago?

Bill Atkinson died last month. As someone who first fell in love with computers because of the original Mac UI, and who is still obsessed with HyperCard forty years after it was launched, I think it's probably fair to say that Atkinson's designs shaped my adult self—my career paths, the way I see the world—as much as anybody else's. I thought I had memorized all the Hypercard lore but reading this lovely obituary from Steven Levy, who knew Atkinson well from his pioneering early reporting on Apple and writing Insanely Great, I discovered that there was another element to the origin story that I hadn't remembered:

One night, [Atkinson] took LSD and wandered out of his home in the Los Gatos hills. Staring into the vast collections of pixels that made up the night sky, he became reenergized, and decided to adopt some of the Magic Slate ideas into software that could run on the Mac.

He designed a program where information—text, video, audio—would be stored on virtual cards. These would link to each other. It was a vision that harkened back to a 1940s idea by scientist Vannevar Bush, which had been sharpened by a technologist named Ted Nelson, who called the linking technique “hypertext.” But it was Atkinson who made the software work for a popular computer. When he showed the program, called HyperCard, to Apple CEO John Sculley, the executive was blown away, and he asked Atkinson what he wanted for it. “I want it to ship,” Atkinson said. Sculley agreed to put it on every computer. HyperCard would become a forerunner of the World Wide Web, proof of the viability of the hyperlinking concept.

Atkinson and Hypercard were on my mind even before he died, thanks to a NotebookLM project I've been focusing on for the past six months, the first preview of which just went live a week ago. Hypercard always had an unusual positioning: it was both a personal productivity tool (organize your cooking recipes!) and a publishing medium (explore my physics 101 hypercard stack!) But in either case, Atkinson had hit on the idea that there could be a new way of bundling information, enhanced by the then revolutionary technology of hypertext. Atkinson thought the best metaphor for it was a stack of magic cards; ultimately what took off was a different kind of bundle: web pages and sites, bound together by links and eventually by search.

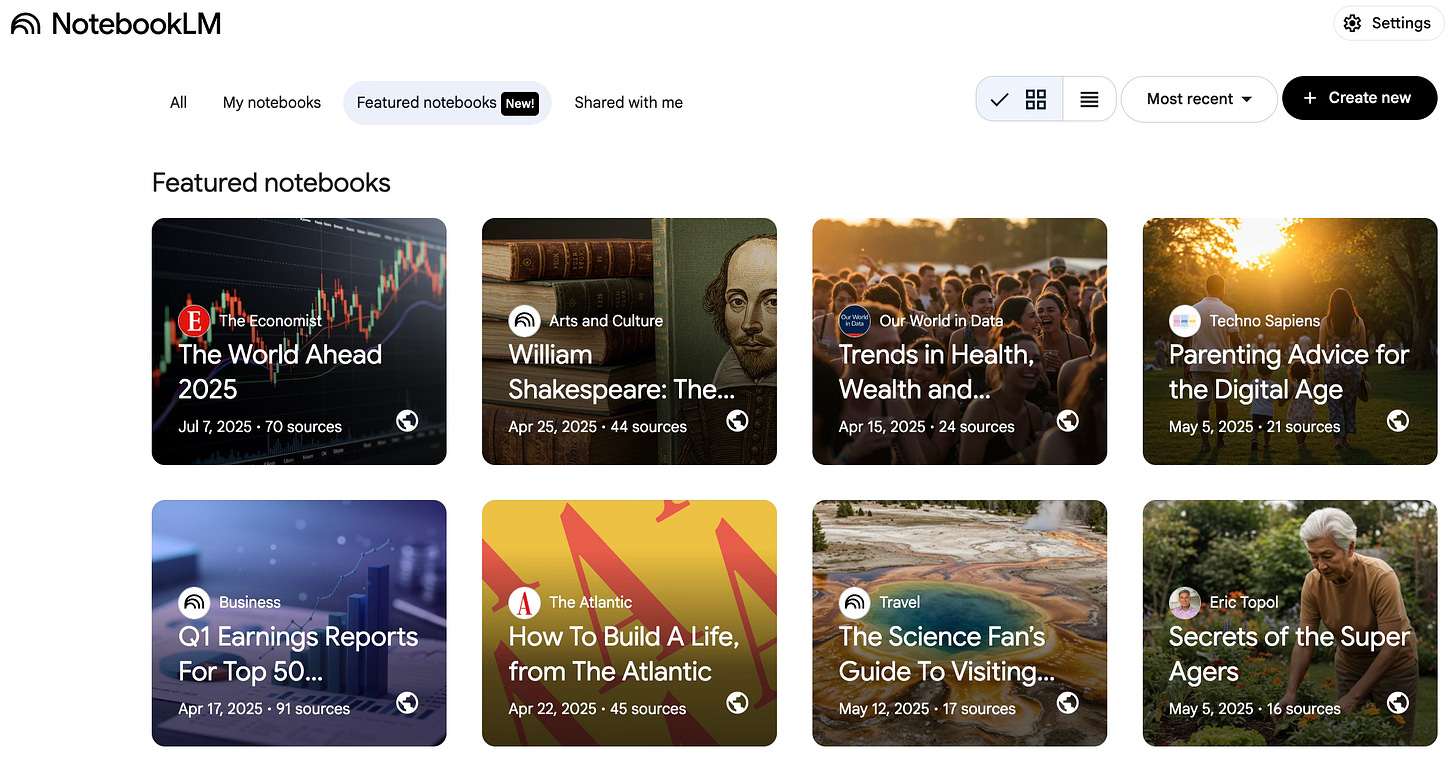

Now, with AI, a new kind of information bundle is possible. For most of its short history, we've described NotebookLM as a tool for understanding and exploring information for your projects. But we also think it could be a distribution platform, amplifying expert knowledge. Last week we rolled out a preview of that vision: Featured Notebooks.

In a way, all of this dates back to a conversation I had with Josh Woodward—who now runs Google Labs and the Gemini app—in late July of 2022, one of the very first I had in Mountain View after joining Labs. We were talking about an idea that had come to us through the work of Kevin Kelly: the concept of "intelligence as a service" that he'd written about many years before, AI that you could tap into on demand like electricity or water. I told Josh that I'd always thought that sounded like a fascinating prospect, though I’d struggled to imagine what it would look like in practice. But what we'd seen with language models, and particularly the source-grounded language models that we were starting to experiment with, had suddenly made it clear to us both how Kelly's intelligence-as-service might actually work, how it might actually give authors and publishers a new platform to share their wisdom with the world.

"We're going to be able to bottle up the knowledge of experts," I said at some point. "And then people will just have that expertise on tap."

Somehow the metaphor stuck: Knowledge bottles. At some point that fall, our then-designer Gabe Clapper created a mock for a future page where you could purchase and download expert collections of knowledge; we called it, irreverently, "the Bottleshop." (It looked quite a bit like the design we are launching today for Featured Notebooks, as it turns out.) I kept encountering the phrase in meetings over the next year, as it spread around Labs and other parts of Google. And every time I would say: love the concept but please don't lock in on "knowledge bottles" as the official name. It was just a passing metaphor!

Naming aside, the underlying premise only grew more compelling over time. General purpose models trained on aggregations of human information were incredibly useful, but imagine how much more useful they would be if they were guided by (or were guides to) knowledge that had been peer-reviewed, edited, researched by experts—knowledge that had a particular point of view. If you're looking for parenting advice, for example, you don't just want the average of all parenting advice across the internet; you want parenting advice from a specialist who you trust.

So you can think of the Featured Notebooks we are launching today as a preview of a potential future where there are thousands of expert-curated notebooks on all sorts of topics that you can add to your own private brain trust, to have the knowledge you need on tap. Our launch lineup includes longevity advice from legendary scientist Eric Topol, bestselling author of Super Agers, alongside expert analysis and predictions for the year 2025 from The World Ahead annual report by The Economist. You can also find an advice notebook based on bestselling author Arthur C. Brooks' "How to Build A Life" columns in The Atlantic, and a science fan’s guide to visiting Yellowstone National Park, complete with geological explanations and biodiversity insights. There's a notebook covering long-term trends in human wellbeing published by the University of Oxford-affiliated project, Our World in Data, and one offering science-backed parenting advice based on psychology professor Jacqueline Nesi’s popular Substack newsletter, Techno Sapiens. For financial analysts and market watchers, there's a notebook tracking the Q1 earnings reports from the top 50 public companies worldwide.

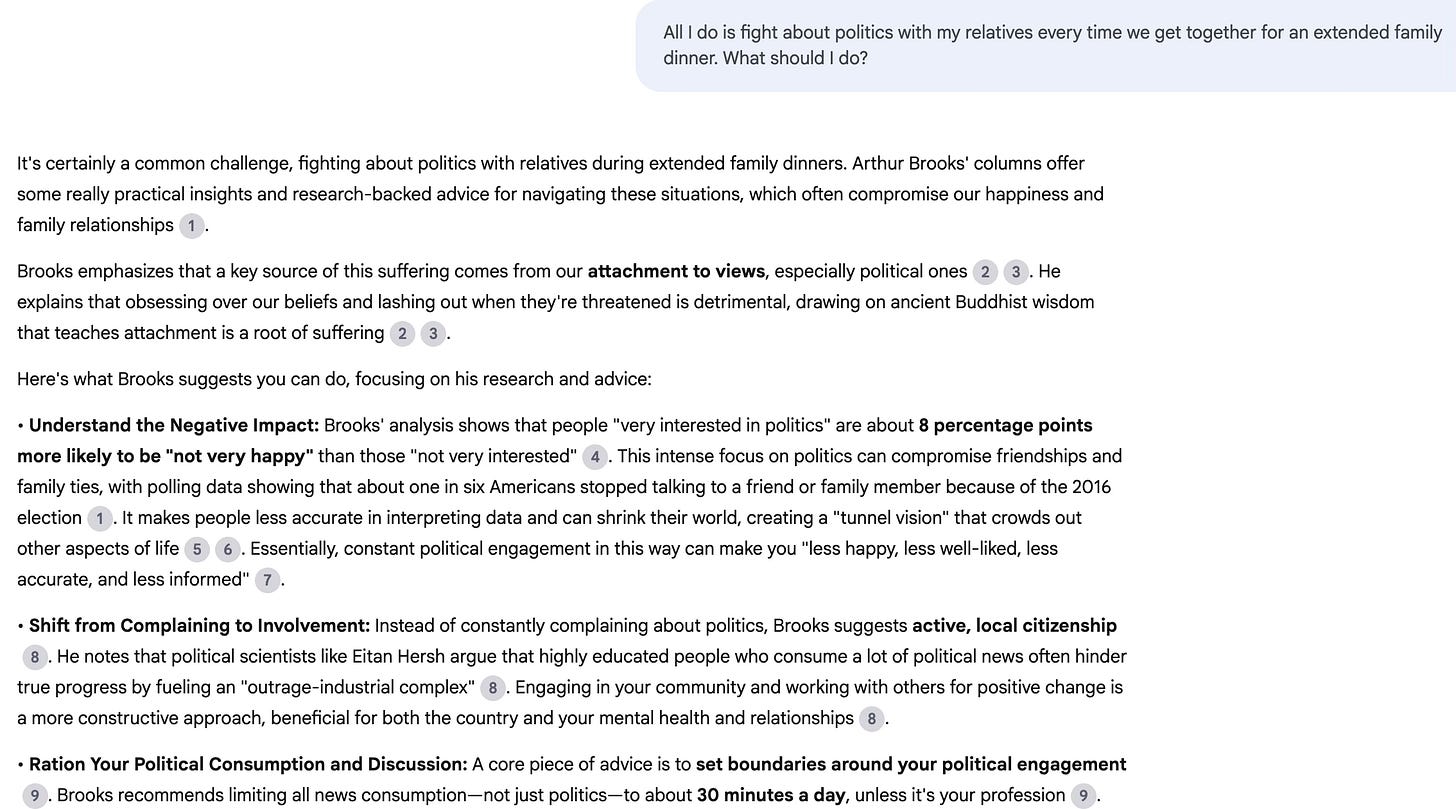

The best way to get a sense of what "bottled knowledge" actually feels like in practice is to open one of these notebooks and ask for advice: ask for a sample itinerary for a 3-day trip to Yellowstone focused on wildlife, or ask for advice on a making a mid-life career change in the "How To Build A Life" notebook from The Atlantic; or ask the experts at The Economist about how global economic trends might impact your industry. I think you'll find that the results are genuinely helpful, and maybe offer a hint of a new way of interacting with an author or publisher's work. Here's an example I really enjoyed from the Arthur Brooks notebook—it's like have an erudite advice columnist writing an essay just for you:

As you might imagine, I'm keenly interested in creating original content designed to be consumed in the notebook format. A curated notebook creates some pretty tantalizing new possibilities for sharing knowledge and expertise—and maybe even storytelling. Your audience can read the original texts in their entirety; they can ask questions or brainstorm ideas through a conversational interface. Students can ask for simpler explanations of complex topics, or listen to Audio Overviews or generate Study Guides to help them master the material. But experts can ask more challenging questions. And all of these interactions can unfold in over 80 languages, no matter what language the original sources were written in.

Imagine all my collected writing on innovation bundled up as a kind of advice notebook that you could consult to help you think through your own creative challenges; or an historical account like “The Man Who Broke The World”, or Enemy Of All Mankind, bundled with all the primary sources and related reading behind the story, designed to be consumed as a linear textual narrative, or an audio overview, or as one of the new formats that we develop over the coming months and years. There's an interesting future for Adjacent Possible here as well; I'd love to be able to offer special notebooks that I curate on a range of topics as one of the perks of a paid subscription.

In the blog post announcing the featured notebooks, there's a wonderful quote from Nick Thompson, CEO of The Atlantic, that made me think of Atkinson and Hypercard all over again: "The books of the future won’t just be static," he said. "Some will talk to you, some will evolve with you, and some will exist in forms we can’t imagine now." Featured Notebooks are a glimpse of that possible future.

One last thing. You'll note that in the Steven Levy obit for Atkinson that we began with, the role of Apple CEO is played by John Sculley, not Steve Jobs. (Jobs had been fired two years before Hypercard's launch.) In 1988, a year after my original indoctrination into tools for thought via Hypercard, Jobs announced his second act as an entrepreneur: the NeXT computer. NeXT had a groundbreaking operating system and graphic interface that would eventually become the basis for OS X, after Jobs' legendary return to the company several years later. But I remember being dazzled (and intrigued) by another part of the announcement: the computer featured a high-capacity optical drive that allowed them to bundle an amazing collection of digital resources on the device: Webster's Ninth New Collegiate Dictionary, Merriam-Webster's Collegiate Thesaurus, and The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations. But the item that really caught my eye was a surprisingly literary addition: the complete works of Shakespeare.

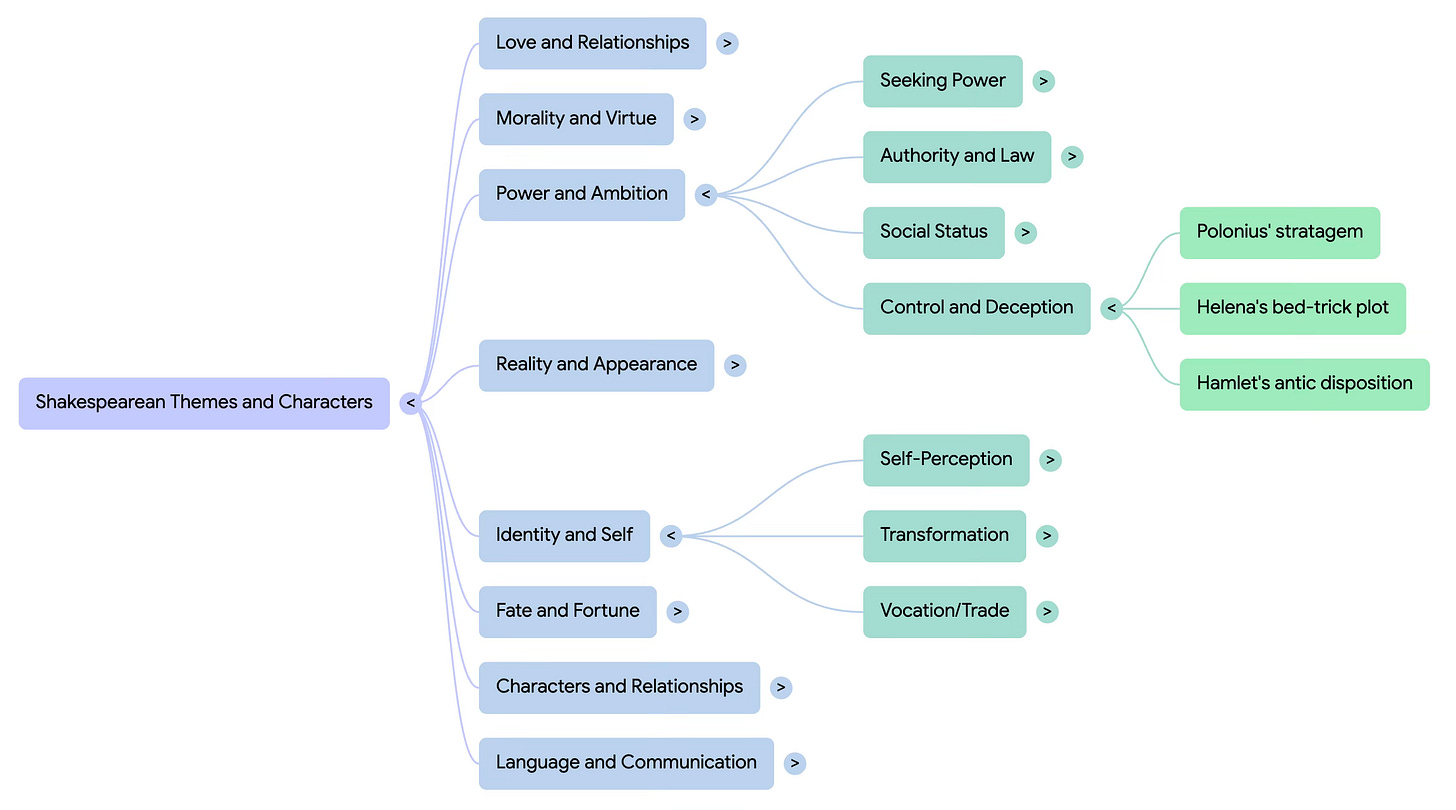

So a few decades later, it seemed right to pay tribute to that history and include a featured notebook with all of Shakespeare's work in our launch lineup. You can read the plays in their entirety; you can ask for help making sense of the Elizabethan English; you can find memorable quotes on just about any topic drawing from all the plays; you can listen to Audio Overviews or review Study Guides to deepen your understanding of Shakespeare’s work. It's pretty magical.

As I was putting together this post, I tracked down the original NeXT brochure, which had this description of the "Digital Librarian" software that came bundled with the computer:

The NeXT System also makes it easy to create your own libraries. The Digital Librarian's cataloging function lets you enter large amounts of information, while automatically creating an index of key words for you. This index then allows you to search your own information - a new "book" in the Digital Library - the same way you would search the dictionary.

As for the kinds of Digital Libraries you can create, there are no limitations. Professors, for example, might build libraries containing a history of their own collected writings. A legal or medical office might construct a library of often used reference materials, while a business might build a reference library of contracts and forms.

Reading that made me think of maybe my favorite magic trick with these new featured notebooks: generating a Mind Map based on all of Shakespeare's writing. In less than a minute, NotebookLM analyzes all the themes and major characters across the plays and sonnets, and organizes them into what is effectively a dynamic, nested index of Shakespeare's entire body of work. And clicking on any of those nodes then takes you directly to an in-depth discussion of how Shakespeare's writing relates to the concept, complete with citations back to the original lines.

There's something truly moving for me, navigating through that Featured Notebook—all this extraordinary technology, inspired by computing legends like Atkinson and Jobs, now being harnessed to map the creative mind of a playwright who died four centuries ago. What would Shakespeare have thought, seeing his work being explored in this way? I honestly have no idea. But I like to think that Atkinson and Jobs would have approved.

I'm confused: who is the expert curating knowledge about Yellowstone? It appears that most of the sources are Park Service webpages, which are public domain, so OK I guess. But isn't "hoovering up public domain webpages" likely to generate AI slop?

Since I was confused, I asked in the chat if all the sources were public domain, and the answer was basically Not necessarily. So I asked if you had the permissions, and the answer was:

<<<Based on our previous conversation, you correctly identified that **not all of the content in the sources provided is in the public domain, and some explicitly states it is offered "with permission from the copyright holders"** [previous turn]. Images and diagrams are also sometimes attributed with a copyright symbol or noted as "Adapted with permission" [previous turn].

Regarding your question, "Do you have the permissions?":

As an AI, I **do not "have" or "hold" permissions** in the legal sense, nor do I acquire or store copyrighted material. My function is to process the text that is provided to me as input during our conversation to generate a response for your query. The sources you are referring to were **provided by you** as the context for my answers.

Therefore, I operate within the confines of the text that you supply to me, and my responses are generated by analyzing and recontextualizing that information based on your requests.>>>

I realize this is just a demonstration. But to me it demonstrates the danger of this alleged publishing model. Other than my personal ethics, what stops me from uploading copyrighted books about Yellowstone to illegally make money with a better Public Notebook than your AI slop?

Wonderful reading. Thanks Steven, I found the story and the insights that emerge from it truly inspiring.

As someone who has a passion for curation, PKM and creating new value out of what is already out there, I want to thank you for reporting on this front.

I look forward to get my hands dirty with Featured Notebooks and to report on what I will discover.