The Forgotten Revolution

Why are the triumphs of public health and medicine a footnote in the history books?

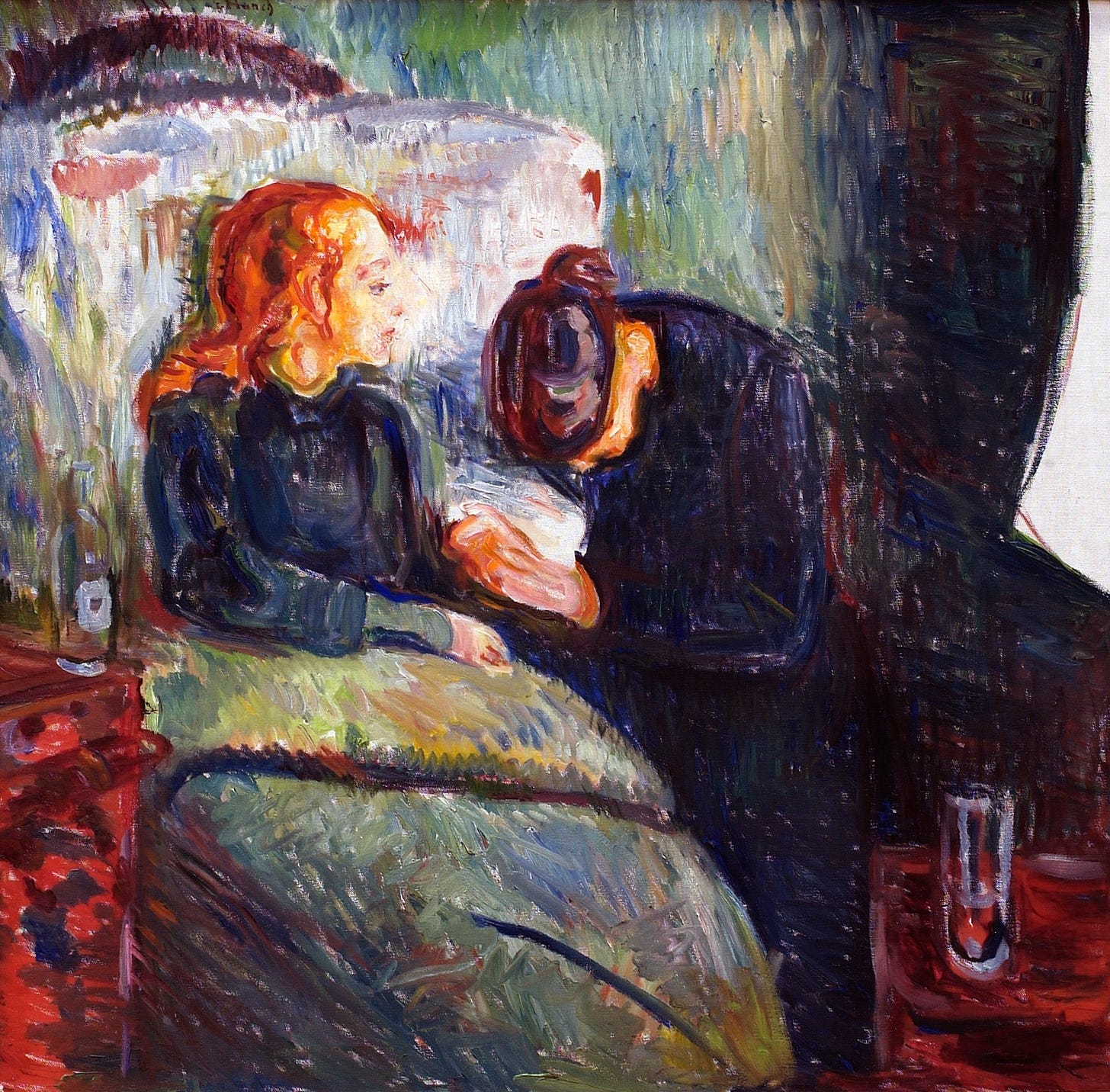

Sometime in 1885 Edvard Munch began working on a painting that came to be called “The Sick Child” — a painting that he would revisit multiple times throughout his career. Munch finished the third iteration—the one you see here—in 1907, thirty years after the tragic event depicted in the painting occurred: the death of his sister Sophie from tuberculosis at the age of fifteen. Sophie’s early death clearly left an indelible scar on Munch himself, but the experience he captured on canvas was a shockingly common one in the nineteenth century, as it had been for all of human history before then: a child in the throes of a terrible and soon-to-be-fatal disease, being tended to by a grieving relative.

Of all the achievements of modern public health and medicine, the most transformative one has to be the radical reduction in childhood mortality over the past century, a seismic shift that turned the experience of “The Sick Child” from a routine fact of life to a rarity. Until very recently, it was simply a given for parents that more than a third of their children died before adulthood, in both the richest countries in the world and the poorest. Today global youth mortality stands at 4%, and in many wealthy countries with robust health safety nets that number is closer to 1%. You can see the long-term view of the change in this astonishing chart from Our World In Data:

The ultimate drivers behind that transformation can be debated, but I think it is inarguable that the overall trend is about as momentous as it gets. Childhood went from being the most dangerous time of your life—unless you were lucky enough to live to be very old—to being the safest. All the other achievements of modernity really pale in comparison to this one. Sure, it’s nice to have refrigeration and electric light and supercomputers in our pockets, but I think most of us would trade all of that to avoid a 40% chance of dying before adulthood.

If you read my book Extra Life, or watched the PBS/BBC series that David Olusoga and I co-hosted, my obsession with this achievement is old news to you. But I wanted to come back to this long-term development from a very specific angle, which is how we teach this history in schools. Or to put it more accurately, how we fail to teach this history in schools.

As an exercise, I did a few keyword searches of an otherwise excellent American history textbook that covers the last 150 years or so. Just to give you some context, the textbook mentions “labor” 226 times, “weapons” 28 times, “automobiles” 20 times, “civil rights” 134 times, and “taxes” 58. Those seem at first glance like appropriate ratios for a textbook of several hundred pages. But when you turn to the achievements of public health and medicine, you get very different results. “Public health” itself is mentioned twice, “sanitation” (in the context of public sanitation, like sewer systems) is mentioned once; the words “antibiotics,” “penicillin,” “vaccines” never appear at all. There is one reference to childhood mortality.

Something is fundamentally distorted in the emphasis here. For reasons that I can’t quite understand, we have decided that military battles and Presidential campaigns and major legislative initiatives constitute events that a high school history student should be informed about, even if many of those events no longer have much impact on our present-day reality. But for some reason, we have written health and medicine out of that canon.

I suppose there are many justifications for studying history, but surely two of the most essential are: 1) to understand the events from the past that shaped the conditions of your own life and experiences, and 2) to recognize patterns from past events that might be relevant to the issues we face as a society today and in the near future. If you happen to be a child, the historical development that most dramatically changed the quality of your life over the past 150 years is the simple but astonishing fact that your odds of dying before adulthood were reduced by a factor of ten. And on the pattern recognition front, we might have less vaccine hesitancy and anti-science belligerence today if we bothered to mention the miraculous development of antibiotics or modern vaccines in our history textbooks.

From the early stages of the project, I’d always imagined Extra Life as a kind of correction to the elisions of that traditional history survey class. The brilliant folks at the Pulitzer Center actually developed a curriculum—based on the PBS series and the New York Times Magazine excerpt from the book—that we rolled out last year when the project first went live. But all along we’d planned for a young reader version of the Extra Life book, modeled after the edition we did for How We Got To Now. And so I’m very excited to share that Viking will be releasing Extra Life: The Astonishing Story of How We Doubled Our Lifespan on January 3. The book is specifically designed for the “middle-grade” audience: I think a ten-year-old with strong reading skills would enjoy it, and it could probably work for a freshman or sophomore in high school as well—though the original Extra Life is written in a style that would also be accessible to many high school readers.

We had our first review last week in Kirkus—they called it “a refreshing change of pace for readers weary of hearing that things are just getting worse”—and the review noted an important challenge that I wrestled with in adapting the book:

Though the author delivers proper nods to Lady Mary Montagu, Alexander Fleming, and like iconic figures, he cogently argues that each advance actually required the work of collaborative networks to effect lasting change. So it was that, for instance, Louis Pasteur might have learned how to sterilize milk, but it was grassroots efforts such as one led by New York City health commissioner Nathan Straus that first persuaded parents to use it and so drastically reduce infant mortality numbers. Collective efforts have also, Johnson writes, given us safer autos and drugs and eradicated smallpox.

Much of my writing on the history of innovation has been predicated on the idea that we tend to over-index on stories of individual inventors, and neglect the impact of collaborative networks in driving progress. (Just think of the thousands of people who had to work together to eliminate smallpox.) But in this young reader version of Extra Life, I decided to organize the chapters around individual people and their stories—Lady Montagu bringing variation to England, W. E. B. DuBois mapping health outcomes in Philadelphia—because I felt like those stories provided a kind of anchor for the middle-grade reader. But as the Kirkus review suggests, I tried to make it clear throughout that these personal threads were all bound up in a broader fabric. If you’re an educator interested in exploring these ideas in the classroom, this new book and the Pulitzer curriculum should make a great combination.

As it happens, just as I was putting the finishing touches on this post this afternoon, I took a break to read a little from Ian McEwan’s new novel, Lessons, and stumbled across a scene where the protagonist as a young boy witnesses a violent automobile accident, followed by a swift response from bystanders and EMTs who rush to the scene to help the two victims. At one point McEwan writes:

He began to cry… He was sorry for the man and woman but that wasn’t it. His tears were for joy, for a sudden warmth and understanding that did not yet have these terms of definition: how loving and good people were, how kind the world was that had ambulances in it that came quickly out of nowhere whenever there was sorrow and pain. Always there, an entire system, just below the surface of everyday life, watchfully waiting, ready with all its knowledge and skill to come and help, embedded within a greater network of kindness he had yet to discover.

There was something about McEwan’s phrasing here that really resonated with me: the recognition that there is “an entire system, just below the surface of everyday life”, quietly protecting us from all kinds of threats. Inventing that “network of kindness” is one of the most extraordinary things we’ve ever done as a species. Why shouldn’t it be front and center in the histories we teach?

Totally agree. More broadly, I think we don't teach enough about the history of technology and how it transformed human life. Students ought to graduate with “industrial literacy”—they need a grounding in how industrial civilization was created and how it operates, the same way they need civics in order to understand how representative government was created and how it operates. But yes, I also agree that public health in particular is neglected even more than the rest of our scientific and technological achievements.

Bravo Steven. I'll send it to Ian McEwan.