The Televised Unconscious

Revisiting Everything Bad Is Good For You's argument about TV complexity with Michael Schur, creator of Parks and Recreation and The Good Place

If you happen to have read a few of my books, you’ll know that there are a handful of themes that run through many of them—sometimes, I’m sure, to the point of self-parody: slow hunches, diverse collaborative networks, intellectual phase transitions, the brain science behind creativity, Dickens, eighteenth-century coffeehouses, and so on. But there are also a few instances where a long-term obsession of mine surfaced in one book but then never really appeared again, even though I’ve continued to be fascinated by it behind the scenes.

One of the best examples of this is the structural analysis I did of television narratives in my 2004 book Everything Bad Is Good For You, which made the then-controversial argument that television had quietly grown far more cognitively complex over the preceding ten years or so on several different axes: the number of plot lines you were compelled to follow over the course of an episode or a season; the number of characters in the imagined universe of the show; the amount of hand-holding the writers did explaining things to you versus leaving you to figure things out on your own. A lot of this work was the legacy of my grad school years studying literature, influenced heavily by my mentor from that period, the literary theorist Franco Moretti, who has a brilliant eye for perceiving the way structural changes in popular narrative connect to wider social transformations. (I originally got to the idea of “exaptations”—which ultimately became a chapter in Where Good Ideas Come From—from an essay Franco wrote about the way literary devices invented in one genre could cross over and be employed by completely different genres in new ways.)

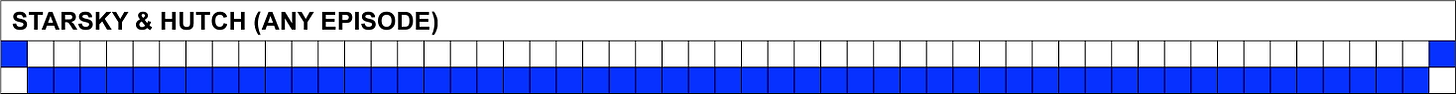

In Everything Bad, I had a lot of fun trying to show the growth in televised complexity by diagramming the structures of a handful of episodes, comparing 70s and 80s shows from my childhood like Dallas with then-contemporary shows like 24. This, for instance, was the chart I created—with the help of my brilliant research assistant for that book, Ivan Askwith—showing the number of distinct storylines woven through an episode of Starsky and Hutch versus Hill Street Blues versus The Sopranos:

I’ve always wanted to go back and revisit those diagrams to document how much more complex television became after I wrote Everything Bad. (Lost came out right around when the book did, and I almost wanted to stop the presses and add an addendum about it.) One major development since 2004 is the step-change in temporal complexity in popular TV. There had been a few provocative experiments in non-chronological storytelling—beyond simple flashbacks—before I wrote Everything Bad, most famously the reverse-chron episode of Seinfeld, which was very hard to enjoy on first viewing. But today, mainstream audiences happily ingest narratives that jump around in time across decades, and even deliberately leave their audiences in the dark about when exactly a given event is happening. The fact that this kind of temporal experimentation can work now on a prime time network drama like This Is Us—which deployed that device to great effect on numerous occasions—shows just how far we’ve pushed the envelope since I wrote Everything Bad.

I mention this whole backstory to explain, in part, why when I sat down to interview Michael Schur—the writer or co-creator of classic shows like The Office, Parks and Recreation, and The Good Place—for the latest TED Interview, the first half of the interview is somewhat weighed down by my rambling “questions” that skip through the last seventy years of television narrative history before I finally manage to ask Schur a proper question. I felt a bit like I had been storing up all these ideas about how television storytelling worked and here I was finally getting to chat with someone who was actually a master at it.

My favorite exchange—which really gets into the weeds—came when I asked Schur about the classic “mockumentary” device of one character glancing silently at the camera, sometimes in eye-roll mode, after another character speaks, a device that is used constantly throughout The Office. Here’s what he said in response:

What's fascinating about it is the reason it works really well throughout 200 episodes of a show. Anything you do 200 times is going to get boring or has the risk of getting boring, right? But the reason that I think it worked really well in The Office is that we were really specific about the different kinds of ways that people looked at the camera—and this is getting really granular, I apologize. A lot of the credit here goes to the actors too, because they didn't all just look at the camera and roll their eyes. Jim looked to the camera like it was his friend, right? [His look was]: finally there's a person who who sees what I have been living for the last however many years. Like: you're my friend and you see this too, right? Dwight would look at the camera like: I am awesome. And you know I'm awesome. Michael would look at the camera very frequently like oh no, because he would say something stupid or racist or whatever, and then would think: oh right, there's a camera here. So they all had these different relationships with that little device, which now is now very common but at the time was brand new for American TV.

I thought this was such a remarkable insight because I have watched all those 200 episodes of The Office and thought to myself many times how effectively the show uses those direct-to-camera glances, but I’d never actually thought about the different ways each character was playing to the camera, even though on some fundamental level I was perceiving those differences, just unconsciously. This is, generally, how structural elements work—in TV sitcoms, but also in the kinds of nonfiction books that I write: the structural decisions about how you organize the narrative or the argument, and the devices you use to propel the narrative or argument forward or make it more interesting, are at the same time incredibly important to the way your audience receives the work, and also, most of the time, completely invisible to them. It’s a bit like the difference between major and minor keys in music; most non-musicians are not consciously aware that they’re listening to one key or another, but somehow they perceive the distinction nonetheless.

Ever since I wrote Everything Bad, I’ve wanted to go back and study the brain science behind these kinds of cultural experiences, where you’ve been trained to enjoy a certain set of aesthetic conventions just through your exposure to them, without anyone actually sitting you down and teaching you the mechanics behind them. What is happening in your mind when you enjoy the comedy of those direct-to-camera glances without actually being aware of how they work? That strikes me as a tantalizing mystery to explore—and even better, you might have to re-watch all 200 episodes of The Office to unpack it.

A quick roundup of a few other end-of-summer developments here: first, there’s a new installment in the Hidden Heroes series, all about the encryption pioneer Phil Zimmermann and his battle with the Feds in the early 1990s over the PGP standard. A number of you have asked about the status of my Wondery podcast, American Innovations, which went on “hiatus” last year. I’m sorry to report that we’ve decided to end that series, after a great run where we produced more than fifty extended narratives with brilliant sound design about the history of innovation. I’m really proud of the work we did on that show—we had a brief tenure as the #1 podcast on iTunes when we launched—but it made sense to move on from it now that I’m hosting the TED Interview. (Sadly—or thankfully, depending on who you talk to—this probably marks the end of my career as a voice “actor.”) And speaking of interesting new chapters, I’ve been appointed to serve as a part-time “visiting scholar” at Google for the next year. I won’t be writing any magazine journalism about the contemporary tech scene during this period to avoid any conflict of interest. I’ll share more about this new adventure here at Adjacent Possible as it develops.

Finally, I’ve got some exciting new plans for this newsletter—connected to the TED Interview—that have been in the works for a while now. I’ll share more next week, so stay tuned…

Steven