Ways Of Flourishing

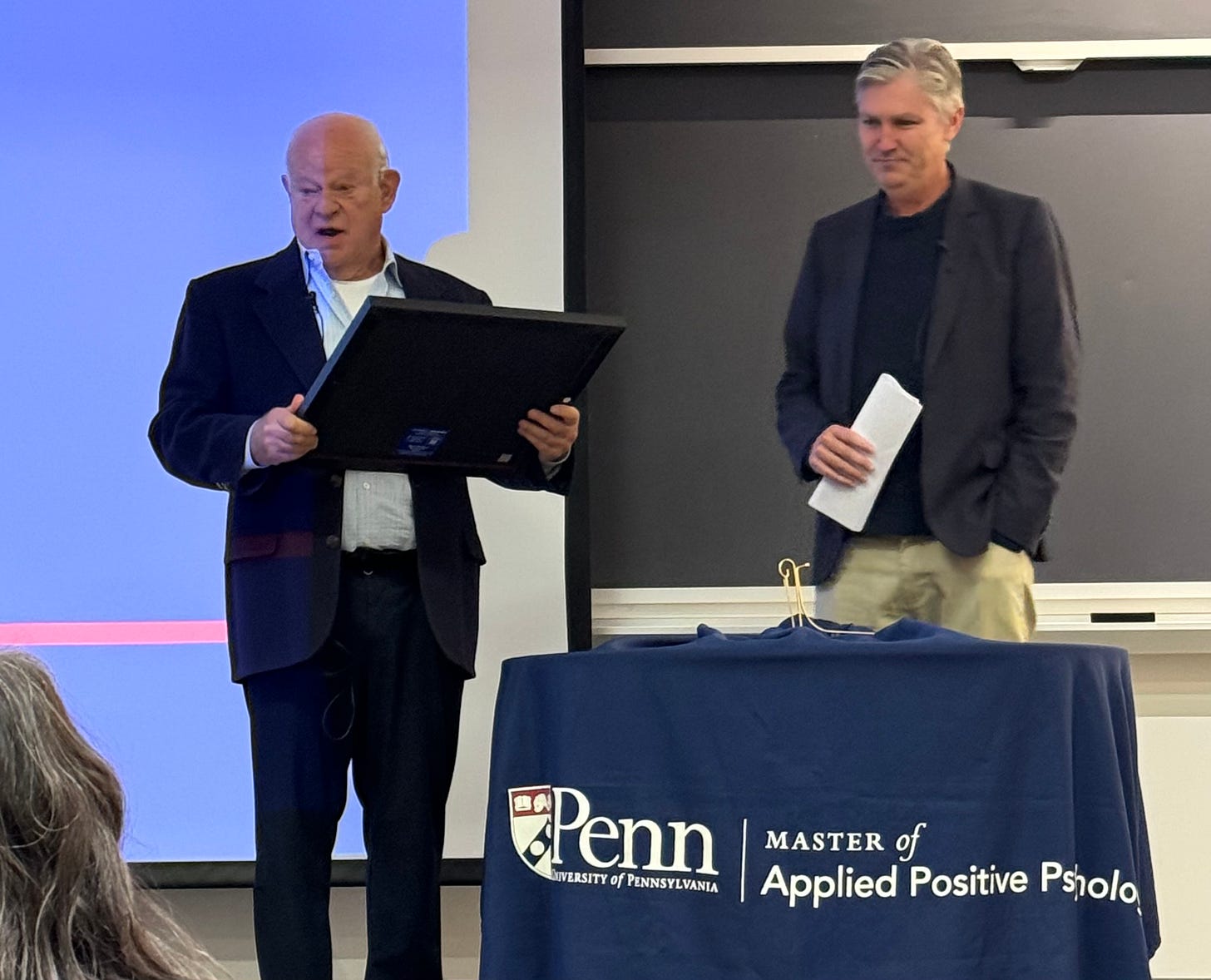

Thoughts on progress and the "compressed 21st century" from my speech accepting the Pioneer Award from the University of Pennsylvania.

[Last weekend, I had the great honor of receiving the Pioneer Award in Positive Psychology from UPenn’s Positive Psychology Center, for my work over the years advancing the cause of human flourishing. It was a very special day for me, in part because the legendary Martin Seligman—who founded the positive psych movement and whose work has inspired me in many ways over the years—actually gave me the award. I put together some remarks for the occasion, which I thought I would share here. I’ve condensed some of the life expectancy material at the beginning because some of it will already be familiar to many Adjacent Possible readers.]

Thank you very much, Marty—what a great honor this is. During yesterday’s presentations, I was very happy to see the word “savoring” included in a list of activities associated with resilient behavior, because I have always given my kids the advice that it’s important to savor moments in your life where something goes well for you professionally or personally, so that you can cement that positive feeling in your mind, and thus be more inclined to seek it out again. And if there were ever an award that deserved savoring, it would be being recognized for advancing the cause of human flourishing!

When the University first reached out to tell me about this honor, Marty suggested that I could talk about my work on the story of human longevity from the Extra Life project. I said I thought the occasion warranted some original material, which I have put together for you here, but I think Marty was right that longevity is a great place to start.

The story at the center of Extra Life was really the story of a single number, and how it changed over the preceding century: the number of years that the average human could expect to live given the conditions in the world at the time of their birth. In other words, life expectancy. A little more than a hundred years ago, at the end of the last global pandemic, human life expectancy stood at around 35 years. A hundred years later, it was more than 70. In the span of just one century, we managed to double the average human lifespan.

To give you a sense of the magnitude of this change—and how it is not something that exclusively happened to the industrialized west—take a look at these two charts. This is the world in 1950. The countries in blue are places where life expectancy has crept above 70 for the first time. It’s just a handful of countries clustered around the North Sea. In red, are all the countries where life expectancy was still below 45.

Compare what the world looked like just 35 years later, in 2015. The blue countries have massively expanded, and there’s not a red country remaining on the map. In fact, there are very few remaining countries with life expectancy below 60, much less 45.

Now, you will sometimes hear people say this kind of progress is actually just a statistical illusion—that we only got better at reducing infant mortality, which was dragging the overall average down because so many people were dying after six days or six weeks. It is true that infant mortality—and childhood mortality—has been dramatically reduced over the last hundred years. It used to be, for all of human history really, that a third of your children would die before reaching adulthood. Now that number is less than one percent. That alone would be a story of extraordinary progress. But the change is actually happening at the other end of the spectrum as well. My grandmother lived to be almost 105. That would have been a massive anomaly a century ago, but it is becoming increasingly common. In fact, centenarians are the fastest growing age demographic in the United States right now.

Take a look at this early infographic by the great Victorian statistician William Farr, which is attempting to show mortality rates by age group in London in the early 1840s.

I find something incredibly heroic about this chart. I mean, here's a guy without computers, without the Internet, without Excel, trying to do something that is incredibly hard and incredibly important. He's trying to look at broad patterns in life and death in a great city, trying to make sense of what is going on. And what the chart reveals is that there was indeed a tragic amount of death among children back then; not just infants, but five-year-olds and ten-year-olds were dying at an alarming rate. But by the same token, almost nobody made it to 85 or 90. And more than half of the population was dead by the age of 45. How many people in this room are older than 45? [More than half the hands go up.] Think about progress and human flourishing in that context. Pretty much the most important prerequisite to flourishing is not being dead!

But there’s another kind of flourishing that comes out of that transformation of human lifespan — something that, appropriately enough, I’ve come to appreciate as I’ve gotten older.

It wasn’t just that my grandmother got to enjoy living a longer life than her ancestors did, but also that she lived long enough to develop deep, enduring relationships with her great-grandchildren. That has an emotional value for sure, but it also has cultural value through the knowledge that gets passed between generations. I’ve written in a number of books about the importance of diversity in driving creativity and decision-making — diversity of background, gender, intellectual fields of expertise and so on. But one element of that story that I think is underappreciated is generational diversity.

A little more than a decade ago my wife and I made the decision to move our family to California for a few years, and for complicated reasons that came out of my career in the tech sector, I ended up making a number of deep friendships out there with people who were close to my parents age—one of whom had actually been in my dad’s class at college, though they didn’t know each other at the time. Those friendships have been intensely important to me, and because all those people have had fascinating intellectual journeys, I’ve learned an enormous amount from their stories of the tumult and possibility of Northern California in the sixties, or the early days of the PC revolution. One of them is actually Larry Brilliant, who played a key role in the eradication of smallpox, one of the most momentous events in the history of life expectancy. (I will return to Larry’s wisdom in a few minutes.) And in turn through these cross-generational friendships, I think they’ve picked up a few interesting signals from my experiences with emerging technologies that they might have otherwise been less attuned to.

And now with the work I’ve been doing with Google, most of the team on the NotebookLM project are much closer to my children’s age than mine, which has been a wonderful addition to my life. I so enjoy going back and forth between those different worlds: I get to be both the young gun and the elder statesman, sometimes all in one day.

If there’s a transfer of fresh knowledge and hard-earned wisdom that comes with interaction across generations, there’s also a widening of temporal scales that emerges when human beings start living longer lives. It’s hard to imagine the deep past, or the distant future, when you’ve only been alive for a decade or two, and if it’s more likely than not that you’ll die before you meet your grandchildren, there’s less incentive to invest in or project forward into that future. But when you think you have a good chance of living for a century or more—in part because your direct relatives are living that long—your temporal horizons expand.

There’s a wonderful moment in Extra Life where I’m interviewing Larry Brilliant about the smallpox eradication project, and he talks movingly about the very last person to contract the disease in the wild, a young girl named Rahima Banu (who survived the infection). In the show, Larry says:

When the smallpox scabs fell off Rahima Banu and were incinerated by the heat, that was the end of an unbroken chain of transmission of variola major going all the way back to Pharaoh Ramses V.

I’ve always been drawn to those kinds of long-term perspectives, where you position yourself—in this case, gloriously free of smallpox—in the larger context of hundreds or thousands of years of human suffering and progress. Some of my California friends even built an entire organization to celebrate that long-term view: the Long Now Foundation, which is dedicated to thinking on the scale of centuries or millennia, encouraging us to get out of the 24-hour news cycle that dominates so much of our lives today. A technologically advanced culture cannot flourish without getting better at anticipating the future. That’s why science fiction matters. That’s why scenario planning matters. That’s why complex software simulations that enable us to forecast things like climate change on the scale of decades matter.

And here I want to bring us back to another idea that Marty Seligman has been an advocate for. Almost ten years ago, he edited a collection of essays called Homo Prospectus which had a huge influence on my thinking about the world. The core idea behind that book was that a defining superpower of human beings is our ability to mentally time-travel to possible future states, and think about how we might organize our activities to arrive at those imagined future outcomes.

“What best distinguishes our species,” he wrote in the introduction to that book, “is an ability that scientists are just beginning to appreciate: We contemplate the future. Our singular foresight created civilization and sustains society. A more apt name for our species would be Homo prospectus, because we thrive by considering our prospects. The power of prospection is what makes us wise. Looking into the future, consciously and unconsciously, is a central function of our large brain.”

It is unclear whether nonhuman animals have any real concept of the future at all. Some organisms display behavior that has long-term consequences, like a squirrel’s burying a nut for winter, but those behaviors are all instinctive. The latest studies of animal cognition suggest that some primates and birds may carry out deliberate preparations for events that will occur in the near future. But making decisions based on future prospects on the scale of months or years — even something as simple as planning a gathering of the tribe a week from now — would be unimaginable even to our closest primate relatives. If the Homo prospectus theory is correct, those limited time-traveling skills explain an important piece of the technological gap that separates humans from all other species on the planet. It’s a lot easier to invent a new tool if you can imagine a future where that tool might be useful. What gave flight to the human mind and all its inventiveness may not have been the usual culprits of our opposable thumbs or our gift for language. It may, instead, have been freeing our minds from the tyranny of the present.

The problem now is that the future is getting increasingly hard to predict, in large part because of what has started to happen with artificial intelligence over the past few years. I’ve spent a lot of my career looking at transformative changes in technology, and I’ve come to believe that what we’re experiencing right now is going to be the most seismic, the most far-reaching transformation of my lifetime, bigger than the personal computer, bigger than the Internet and the Web. And while there is much to debate about what the impact of this revolution is going to be for the job market, for politics, and just about any other field, there is growing consensus that it is going to provide an enormous lift to medicine and human health. The Nobel Prize for chemistry going to the AlphaFold team last week was arguably the most dramatic illustration of the promise here. Earliest this month, Dario Amodei—the founder of the AI lab Anthropic, makers of Claude–published a 13,000 word piece on where he thought we were headed with what he calls “powerful AI” in the next decade or two. The line that really struck me in the piece was this:

My basic prediction is that AI-enabled biology and medicine will allow us to compress the progress that human biologists would have achieved over the next 50-100 years into 5-10 years… a compressed 21st century.

Whether or not something that dramatic does come to pass—and I think we have to take the possibility of it seriously—it seems clear that given the kind of biological and medical advances that AI will likely unlock, there is significant headroom left in the story of extended human lifespan, perhaps even a sea change in how we age. That is, on one level, incredibly hopeful news. But it is also the kind of change that will inevitably have enormous secondary effects. To understand just how momentous those changes could be, take a look at this chart:

That’s the 6,000 year history of human population growth. You might notice, if you really squint your eyes, that something interesting appears to happen about 150 years ago. After millennia of slow and steady growth, human population growth went exponential. And that’s not the result of people having more babies—the human birth rate was declining rapidly during much of that period. That’s the impact of people not dying. And while that is on one level incredibly good news, it is also in a very real sense one of the two most important drivers of climate change. If we had transferred to a fossil-fuel-based economy but kept our population at 1850 levels, we would have no climate change issues whatsoever—there simply wouldn’t be enough carbon-emitting lifestyles to make a measurable difference in the atmosphere.

The key idea here is that no change this momentous is entirely positive in its downstream effects. Trying to anticipate those effects, and mitigate the negative ones, is going to take all of our powers of prospection.

When I was putting together my thoughts for this talk, my mind went back to the one time I spoke with Marty, about five years ago, when I was writing about cognitive time travel for the Times Magazine. As usual, I was incredibly behind in actually doing the reporting for the piece, and I’d called Marty desperate for a few quotes on a tight deadline. He very generously found time for me, but he had to do the call from an animal hospital, because as it happens he and his family were in the middle of putting their dog down. So our very first moments in conversation with each other plunged right into the depths of loss and grieving and the strange bonds that form between animals and humans. There was no small talk.

As I said earlier, death is, in the most basic sense, the termination point of human flourishing. But it’s also the shadow that hovers over us while we are still alive. We have done so much to minimize that shadow over the past century or two, going from a world where it was the norm for a third of your children to die before adulthood to a world where less than one percent do. But what does it mean for human flourishing if that runaway life expectancy curve that we’ve been riding for the past century keeps ascending? What does it mean if AI starts out-performing us at complex cognitive tasks? How do we flourish in that brave new world? Do we take on a new responsibility—not just ensuring the path of human flourishing, but also the flourishing of our AI companions? These are all difficult questions precisely because of time. The rate of change is so extreme right now we don't have as much time to learn, and adapt. The doubling of human life expectancy was a process that really unfolded over two hundred years, and we’re still dealing with its unintended consequences. What happens if that magnitude of change gets compressed down to a decade?

I don’t know the answers to those questions yet, I’m sorry to report. But maybe spelling them out together helps explain something about what I’ve tried to do with my career, which I think from afar can sometimes seem a bit random, bouncing back and forth between writing about long-term decision making or exploring the history of human life expectancy and building software with language models. This award is called the Pioneer Award, and while I’m deeply honored to receive it, I don’t think of myself so much as a pioneer in any of these fields, but rather as someone who has consistently tried to find a place to work that was adjacent to the most important trends in human flourishing, so that I could help shine light on them, explain them to a wider audience, and in the case of my work with AI, nudge them in a positive direction to the best of my ability. That you all have recognized me for this work—pioneer or not—means an enormous amount to me. You can be sure I will do my best to savor it.

You are one of my favorite thinkers and authors.

I think you are amazing. I love the lane you have found for your intellectual and historical investigations. So thought provoking and endlessly interesting. thank you for continuing to dig.