A Secret History Of Monopoly

The Long-Suppressed Radical Politics Behind America’s Favorite Board Game.

[You’re reading a post from my Adjacent Possible newsletter. Sign up to receive more essays like this one in your inbox.]

There was a serendipitous overlap between my Twitter feed and this newsletter earlier this week: as I was posting the first part of my exchange with Chris Dixon, discussing the ways in which game worlds can often anticipate new forms of social or economic organization, I happened across this very funny tweet from Matt Yglesias:

My first thought was: I probably played six thousand hours of Monopoly with my kids, and never once did this occur to me. But my second thought — no doubt primed by my conversation with Chris — was that Monopoly actually has a long and fascinating history at the vanguard of radical ideas about land use and progressive politics, a history that was completely suppressed for decades. I wrote about it the “Games” chapter of my book Wonderland, and so I thought it would be fun to revisit that story here. The canonical account — promulgated by Parker Brothers for decades — was that Monopoly had been invented by a plucky entrepreneur named Charles Darrow in the middle of the Depression. But in fact, Monopoly began more than thirty years earlier, with a game patented in 1903 by a brilliant and multitalented political radical named Lizzie Magie. It was called The Landlord’s Game.

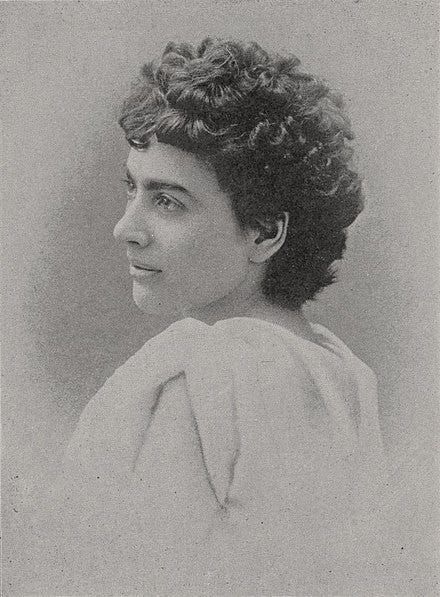

Born in Illinois in 1866, Magie had an eclectic and ambitious career even by suffragette standards. She worked at various points as a stenographer, poet, and journalist. She invented a device that made typewriters more efficient, and worked part-time as an actress on the stage. For a long time, her greatest claim to fame came through an act of political performance art, placing a mock advertisement in a local paper that put herself on the market as a “young woman American slave”—protesting the oppressive wage gap between male and female salaries, and mocking the mercenary nature of many traditional marriages.

Magie was also a devotee of the then-influential economist Henry George, who had argued in his bestselling 1879 book Progress and Poverty for an annual “land-value tax” on all land held as private property—high enough to obviate the need for other taxes on income or production. Many progressive thinkers and activists of the period integrated “Georgist” proposals for single-tax plans into their political platforms and stump speeches. But only Lizzie Magie appears to have decided that radical tax reform might make compelling subject matter for a board game.

After patenting The Landlord’s game in 1903, she published a brief outline of the game the following year in a Georgist journal called Land and Freedom. Her description would be immediately familiar to most of us today, more than a century later:

Representative money, deeds, mortgages, notes and charters are used in the game; lots are bought and sold; rents are collected; money is borrowed (either from the bank or from individuals), and interest and taxes are paid. The railroad is also represented, and those who make use of it are obliged to pay their fare, unless they are fortunate enough to possess a pass, which, in the game, means throwing a double. There are two franchises: the water and the lighting; and the first player whose throw brings him upon one of these receives a charter giving him the privilege of taxing all others who must use his light and water. There are two tracts of land on the board that are held out of use—are neither for rent nor for sale—and on each of these appear the forbidding sign: “No Trespassing. Go to Jail.”

Magie had created the primordial Monopoly, a pastime that would eventually be packaged into the most lucrative board game of the modern era, though Magie’s role in its invention would be almost entirely written out of the historical record. Ironically, the game that became an emblem of sporty capitalist competition was originally designed as a critique of unfettered market economics. Magie’s version actually had two variations of game play, one in which players competed to capture as much real estate and cash as possible, as in the official Monopoly, and one in which the point of the game was to share the wealth as equitably as possible. (The latter rule set died out over time—perhaps confirming the old cliché that it is simply less fun to be a socialist.) Either way you played it, however, the agenda was the same: teaching children how modern capitalism worked, warts and all. “Let the children once see clearly the gross injustice of our present land system,” she argued, “and when they grow up, if they are allowed to develop naturally, the evil will soon be remedied.”

The Landlord’s Game never became a mass hit, but over the years it developed an underground following. It circulated, samizdat-style, through a number of communities, with individually crafted game boards and rule books dutifully transcribed by hand. Students at Harvard, Columbia, and the Wharton School played the game late into the night; Upton Sinclair was introduced to the game in a Delaware planned community called Arden; a cluster of Quakers in Atlantic City, New Jersey, adopted it as a regular pastime. As it traveled, the rules and terminology evolved. Fixed prices were added to each of the properties. The Wharton players first began calling it “the monopoly game.” And the Quakers added the street names from Atlantic City that would become iconic, from Baltic to Boardwalk.

It was among that Quaker community in Atlantic City that the game was first introduced to a down-on-his-luck salesman named Charles Darrow, who was visiting friends on a trip from his nearby home in Philadelphia. Darrow would eventually be immortalized as the sole “inventor” of Monopoly, though in actuality he turned out to be one of the great charlatans in gaming history. Without altering the rules in any meaningful way, Darrow redesigned the board with the help of an illustrator named Franklin Alexander, and struck deals to sell it through the Wanamaker’s department store in Philadelphia and through FAO Schwarz. Before long, Darrow had sold the game to Parker Brothers in a deal that would make him a multimillionaire.

For decades, the story of Darrow’s rags-to-riches ingenuity was inscribed in the Parker Brothers rule book: “1934, Charles B. Darrow of Germantown, Pennsylvania, presented a game called MONOPOLY to the executives of Parker Brothers. Mr. Darrow, like many other Americans, was unemployed at the time and often played this game to amuse himself and pass the time. It was the game’s exciting promise of fame and fortune that prompted Darrow to initially produce this game on his own.” Both the game itself—and the story of its origins—had entirely inverted the original progressive agenda of Lizzie Magie’s landlord game. A lesson in the abuses of capitalist ambition had been transformed into a celebration of the entrepreneurial spirit, its collectively authored rules reimagined as the work of a rags-to-riches lone genius.

Magie was still alive when Darrow’s version hit the market, and she publicly accused Parker Brothers of stealing her intellectual property, which resulted in a settlement that mostly involved Parker Brothers agreeing to publish some of Magie’s other games, without acknowledging her as Monopoly’s original game designer.

Reading through this story now, it occurs to me that there really needs to be a Queen’s Gambit/Marvelous Mrs. Maisel-style streaming series about Lizzie Magie’s life. (Who’s up for crowdfunding that?) But until that’s a reality you can read more about the long interconnection between games and political change—along with many other stories about play and innovation generally—in Wonderland, which happens to have my favorite jacket design of any of my books. (Note the way we snuck The Landlord’s Game into the backdrop.)

You’re reading a post from my Adjacent Possible newsletter. Sign up to receive more essays like this one in your inbox. There are also two paid subscription tiers to Adjacent Possible: for $5/month or $50/year, you’ll have access to new original essays from me, and exclusive email-based conversations with some of the smartest people I know. This fall’s lineup includes the legendary Stewart Brand, Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks author Rebecca Skloot, Think Again author Adam Grant, New York Times columnist Ezra Klein, and Rationality author Steven Pinker.

There’s also an “Ideal Reader” tier for $120/year: for that you get all the advantages of the paid subscription but I will also send you a signed, personalized copy of each new book I write, starting with my latest book, Extra Life.