Capturing and Colliding

How do you retain and remix ideas from other people’s minds? A 300-year-old productivity hack might be the key. Part two of a series on designing a workflow for thinking.

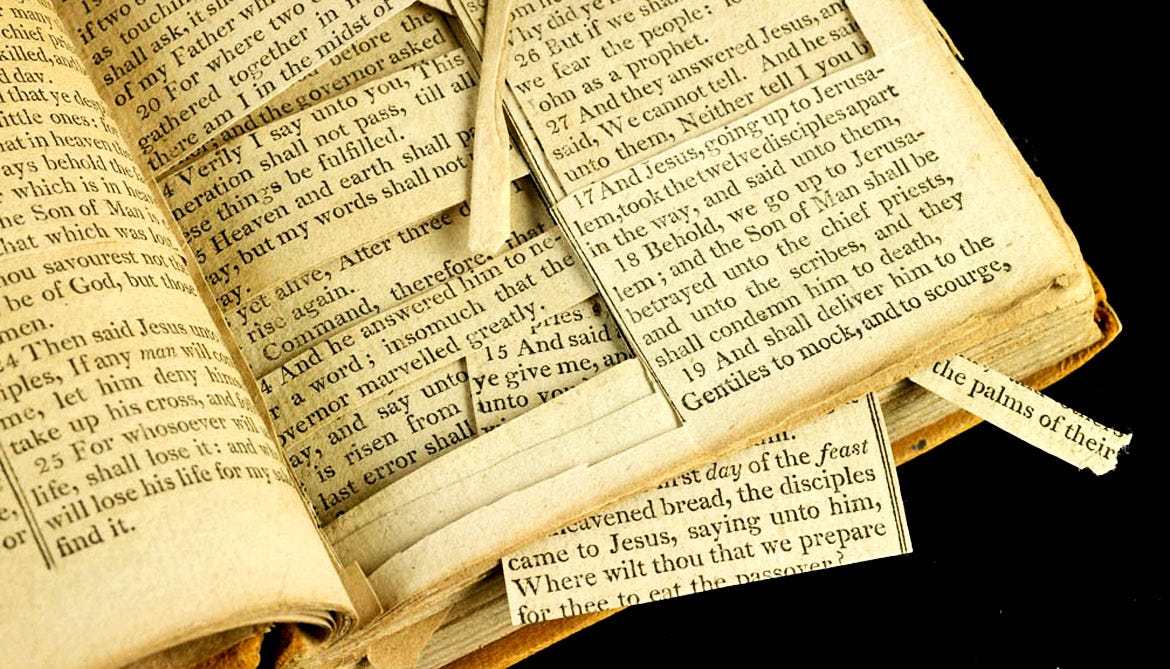

“Unlike modern readers, who follow the flow of a narrative from beginning to end, early modern Englishmen read in fits and starts and jumped from book to book. They broke texts into fragments and assembled them into new patterns by transcribing them in different sections of their notebooks. Then they reread the copies and rearranged the patterns while adding more excerpts. Reading and writing were therefore inseparable activities. They belonged to a continuous effort to make sense of things, for the world was full of signs: you could read your way through it; and by keeping an account of your readings, you made a book of your own, one stamped with your personality.”

—- Robert Darnton

In part one of this series, I wrote about the importance of capturing your early-stage hunches, and revisiting them over time in the context of new ideas or projects. But of course any attempt to design a workflow for thinking has to incorporate ideas that originate in other people’s minds too. Over the years, as I’ve experimented with different ways of organizing my creative process, one of the central challenges has turned out to be figuring out the best technique for storing quotations from whatever I happen to be reading.

Managing a private archive of quotes is a venerable tradition, as it turns out. In my book Where Good Ideas Come From, I wrote about the Enlightenment-era practice of maintaining what was then called a “commonplace book”:

Scholars, amateur scientists, aspiring men of letters—just about anyone with intellectual ambition in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries was likely to keep a commonplace book. The great minds of the period—Milton, Bacon, Locke—were zealous believers in the memory-enhancing powers of the commonplace book. In its most customary form, “commonplacing,” as it was called, involved transcribing interesting or inspirational passages from one’s reading, assembling a personalized encyclopedia of quotations. There is a distinct self-help quality to the early descriptions of commonplacing’s virtues: maintaining the books enabled one to “lay up a fund of knowledge, from which we may at all times select what is useful in the several pursuits of life.”

I didn’t realize it at the time, of course, but the Hypercard app I designed when I was a sophomore in college—which I discussed in the introduction to this series—was really my attempt to build a commonplace book using the new tools made possible by personal computers and the graphic interface. For more than a decade after that initial experiment, the whole process of storing interesting quotations was hamstrung by the fact that the vast majority of the material that I read was in print form: books, magazines, print journals. When I began writing for a living in earnest in the late 1990s, I used employ research assistants for my books, both to track down obscure scholarly articles in libraries, but mostly just to type up the quotations from print sources so that I would have them in digital form. It was incredibly time consuming, but the payoff of having all the quotes sitting on my hard drive, in a searchable format, was worth the cost.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Adjacent Possible to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.