Thinking Across Generations

In the latest installment of the creative workflow series: the connection between mixed-gender groups and innovative thinking, and the value of cultivating generational diversity in your life.

A few weeks ago, Adam Grant tweeted a brief reference to a new paper published by a team of scholars from Northwestern, Michigan State, and NYU, published in the Proceedings of the National Academic of Sciences:

The headline of the paper caught my eye: “Gender-diverse teams produce more and higher-impact scientific ideas.” Or as Adam summarized it in his tweet: “Similarity breeds groupthink. Variety fuels deeper reflection and broader learning.”

I was interested in exploring the paper’s findings for a number of reasons. To begin with, I’ve written quite a bit over the years about the connection between diversity and creativity, particularly in my book Farsighted, which looked at some of the surprising reasons why diverse groups make more creative decisions. But the study also caught my eye because it resonated with a lot of what we’ve been discussing in this series on creative workflows. So many of these posts have explored the question of how you build serendipity and surprise into your thinking space. And of course, one crucial way to do that is to bring other people into that space who think differently from the way you do.

The connection between diverse groups and innovative thinking has a long history; Scott E. Page’s book The Difference mapped out a lot of this terrain years ago. Page and his colleague Lu Hong referred to this as the “diversity trumps ability” theory, based on research laid out in this influential 2004 paper. The Page/Hong idea is that if you have to choose between a random collection of people to solve a complicated problem and a homogenous group of high-ability people, you’ll get better results from the random, diverse group. There have been countless studies since then that have assembled small groups of varying composition—all men vs. mixed gender, heterogeneous or homogeneous groups in terms of racial or economic backgrounds—and asked them to complete some task that involve creative thinking, or make a complex decision that requires them to contemplate and synthesize many variables — and the results consistently point to a significant “diversity bonus” that improves the originality of thought that group produces collectively.

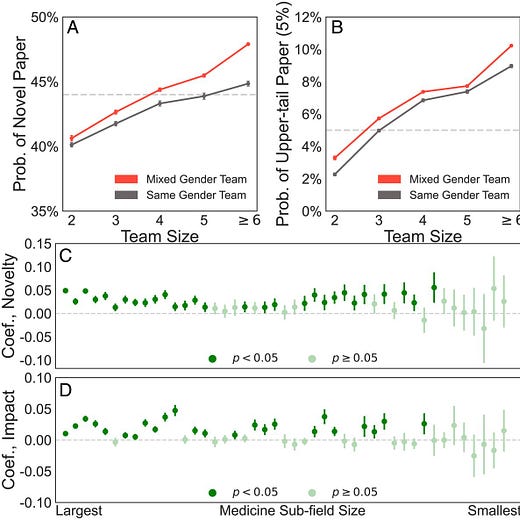

What I like about this new PNAS paper is the way it tries to analyze group creativity at scale, by analyzing millions of existing scientific papers in the archive. The study tracks two key measures of success: the influence of each paper, and its novelty.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Adjacent Possible to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.