The Blank Page Revolution

How paper changed the way we think.

A few months ago, I finally picked up a book that I'd been meaning to read since it came out last year, Roland Allen's The Notebook: A History of Thinking on Paper. I suspect I had put off reading it for a couple of reasons: for starters, it felt a little bit like a busman's holiday to read a book about notebooks in my spare time, while spending my working hours developing NotebookLM. And I suppose I assumed I already knew most of the material, having written extensively about the long history of keeping notes and commonplace books. Both in books like Where Good Ideas Come From, and even here at Adjacent Possible, I’ve spent a lot of time writing about the intellectual rewards of jotting things down. But Allen's book turns out to be filled with facts and observations that I hadn't encountered before, and I came away from it with a cascade of new ideas and connections.

The most surprising insight, I think, revolves around the significance of the fundamental substrate of all modern notebooks until the digital age: paper. Before reading Allen's book, I had mostly thought about paper in terms of Gutenberg and the printing press democratizing knowledge and information by making it much easier to publish and read printed information in the form of books. But somehow I hadn't fully thought through the more intimate revolution that it enabled—a revolution of self-knowledge and private record-keeping, executed not with a printing press but with a pen.

The very idea of a “notebook”—a cheap, lightweight device for capturing stray thoughts—is a relatively recent invention, because for most of human history the materials for capturing those thoughts were anything but cheap and lightweight. Writing itself has been around for at least five thousand years, but for most of that long run, the surfaces people wrote on were comically ill-suited for the kind of casual jotting that we associate with notebooks. Before the arrival of paper, if you wanted to keep track of your thoughts, you had to turn to a whole menagerie of cumbersome technologies: tablets made of hinged wood and ivory, filled with beeswax that you could inscribe with a stylus; papyrus scrolls; or the most durable of the lot, parchment, made from scraped animal hides, which was so expensive to produce that a single notebook might require the skins of an entire flock of sheep.

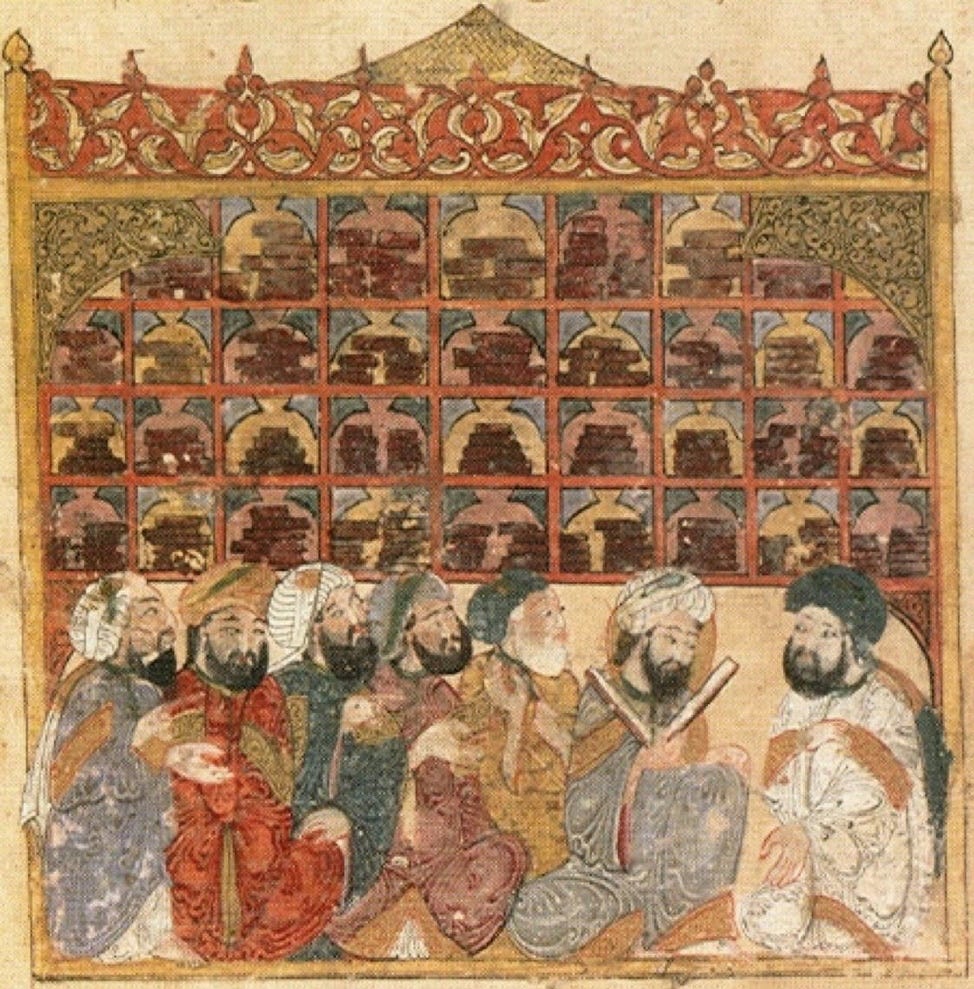

It’s a historical connection that honestly I should have grasped earlier. A few years ago, in my book Wonderland, I wrote about the astonishing flourishing of intellectual and commercial life in Baghdad during the Abbasid Caliphate, starting around the year 800 CE. The city was arguably the greatest single innovation hub on the planet at the time, a place where you could find magically lifelike automatons, oil-based streetlights, and state-of-the-art aqueducts. In Wonderland, I'd written about the legendary House of Wisdom, which was a strange hybrid of library, translation bureau, and Bell Labs-style R&D lab, where classic works from the Greco-Roman age were translated and stored in what was almost certainly the most comprehensive library in the world at that time.

This explosion of intellectual energy didn't just appear out of thin air. The new ideas, I argued, were themselves flowing through the city along with silks and spices from the East, because Baghdad sat at the nexus of the global trade routes of the age. But I'd missed one of the key technological platforms that made all that creativity possible: the arrival of relatively cheap, mass-produced paper, an invention that had made its way west along the Silk Road from China.

The Abbasids embraced paper with an astonishing fervor, with their vast libraries and entire streets filled with booksellers, a good six centuries before Gutenberg. But these weren't "books" in the way we think of them today. The Abbasids had mastered the codex format—binding individual sheets of paper together, just like a modern paperback, which was a massive improvement over traditional scrolls. But they didn't have movable type. There was no way to mass-produce these texts. Every single copy had to be transcribed by hand, a painstaking process that made each volume a significant investment, even with the cheaper paper.

So if you think of the development of book publishing as a linear progression, there's an easy-to-imagine ladder that ascends from the invention of paper, to the invention of the codex form factor, to the invention of movable type, which ultimately produces the modern archetype of a mass-produced book, and then triggers all the secondary cultural effects that we associate with the post-Gutenberg era: the Reformation, the scientific revolution, commercial pornography, and more.

But there's another branching path on that evolutionary tree that Allen's account highlights: paper made casual, personal notetaking far easier and far cheaper. And that casual notetaking didn't just stay in Baghdad. By the 1200s, Italian merchants who traded with the Islamic world had recognized the superiority of paper over parchment. Paper factories, using mechanized water power, sprang up in towns like Fabriano, churning out thousands of pages a day at a fraction of the cost of animal hides. Think of Da Vinci's legendary notebooks from the 1400s where he developed so many of his ideas. As Allen puts it, those ideas were enabled by the cutting-edge "information technology" of paper.

If you've been a longtime reader of Adjacent Possible, or followed some of the things I've written about NotebookLM, you might imagine that this is all a big setup for the ultimate emergence of the commonplace book, the defining "tool for thought" of the Enlightenment. And you wouldn’t be wrong—that revolutionary tradition is a crucial branch on this particular evolutionary tree. But Allen’s book reminded me that there was another, equally significant, tradition of note-taking that was also enabled by cheap paper, one that would prove to be just as influential as the commonplace book, though in a completely different domain. The commonplace book was a tool for organizing ideas. The other tradition involved keeping a notebook where you organized your money—bookkeeping in a word.

Financial records are as old as writing itself, of course. For millennia, merchants and administrators had scratched out inventories and receipts on clay tablets or papyrus scrolls. But those older technologies were too clunky and expensive for day-to-day accounting. "Paper had another key advantage over parchment for financial record-keeping: ink soaks into paper, making it permanent," Allen writes. "Parchment, on the other hand, could be scraped clean and re-used, which opened the door to fraud. With cheap, secure paper notebooks at their disposal, the Italian merchants developed the cornerstone of modern accounting: the system of double-entry bookkeeping."

Now the cornerstone of all financial bookkeeping, double-entry’s innovation of recording every financial event in two ledgers (one reflecting a debit, the other a credit) allowed merchants to track the financial health of their businesses with unparalleled accuracy. We do not know if the method originated in the mind of a single visionary proto-accountant, or whether the idea emerged simultaneously in the minds of multiple entrepreneurs, or whether it was passed on by Islamic entrepreneurs who may have experimented with the technique centuries before. Whatever its roots, the technique first became commonplace in the trade capitals of Italy—Genoa, Venice, and Florence—as the merchants of the early Renaissance shared tips among themselves on how best to manage their finances. What makes the history of double-entry so fascinating is the simple fact that no one seems to have claimed ownership of the technique, despite its immense value to a capitalist enterprise. I wrote about the irony here briefly in Good Ideas: one of the essential instruments in the creation of modern capitalism appears to have been developed collectively, circulating through the liquid networks of Italy’s cities. Double-entry accounting made it far easier to keep track of what you owned, but no one owned double-entry accounting itself.

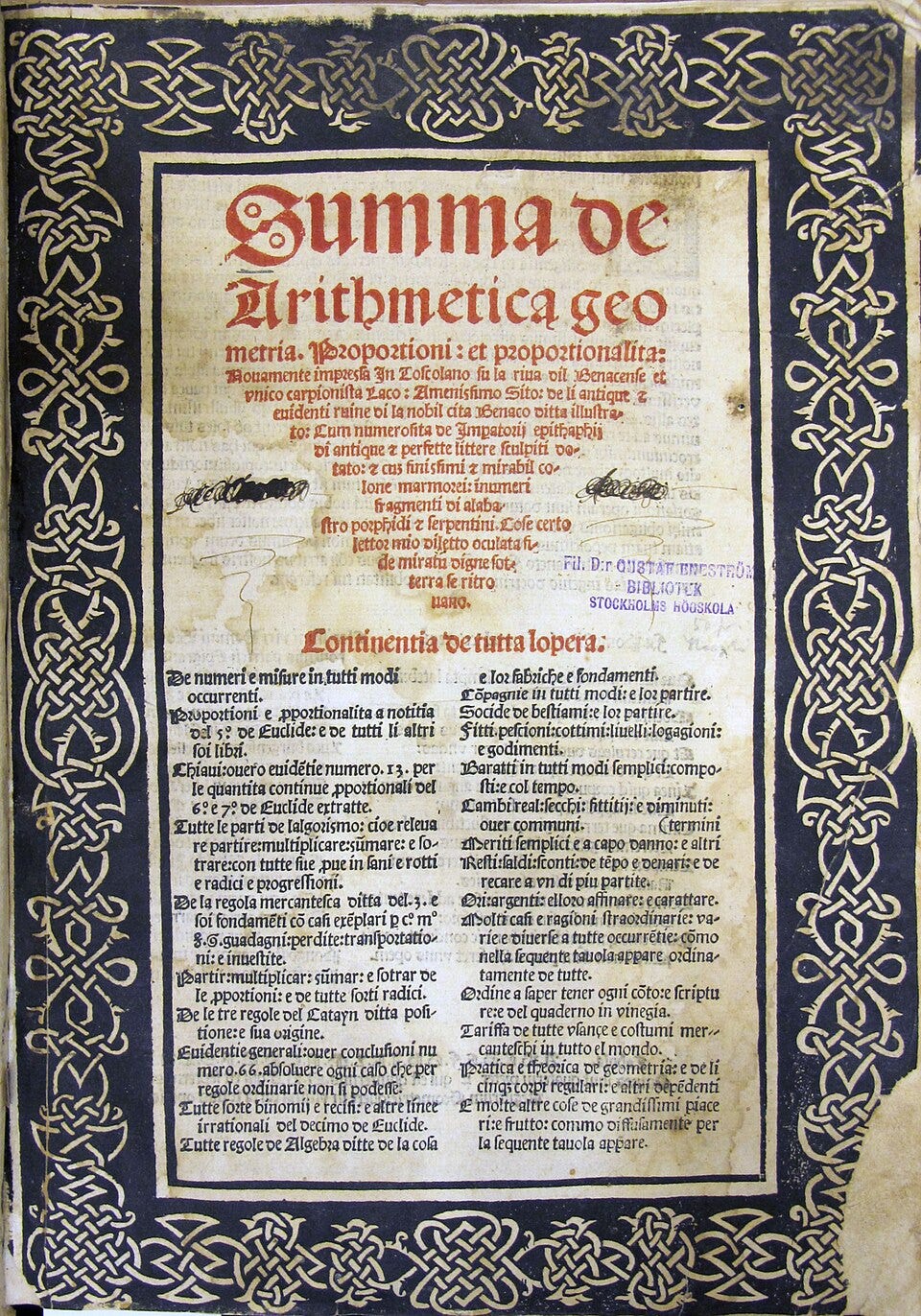

But for all its brilliance, double-entry accounting remained a kind of guild secret for more than two centuries, a technique passed down informally between merchants. It took another revolutionary information technology—the printing press—and an immensely talented polymath to turn the practice into a global standard. The polymath’s name was Luca Pacioli, a Franciscan friar and mathematician who was a close friend and collaborator of da Vinci. In 1494, Pacioli published a massive encyclopedia of mathematical knowledge, Summa de Arithmetica, written in vernacular Tuscan so it would be accessible to a wide audience. Buried inside its 600-plus pages was a section that provided the first published description of the double-entry system, making its principles clear to anyone with a basic education. Pacioli’s book became a bestseller, and soon “the Italian method,” as it was called, became the foundation for mercantile practice across Europe. It was history's first example of a genre that would come to dominate the bestseller lists: a how-to-succeed-in-business advice manual.

The history of paper and the notebook has a striking parallel to another story we told in How We Got To Now—the story of glass. For millennia, humans had known about the magnifying properties of curved glass, but had found very little practical use for it. It wasn't until the late 1200s that someone—working with the breakthrough technology of transparent glass that had been concocted by the glassmakers of Murano—had the brilliant idea of shaping glass into small discs to be worn as spectacles. Reading glasses were a revolutionary tool for thought, extending the intellectual life of scholars by decades. (And making it possible for them to continue to maintain their own notebooks, well after the onset of presbyopia.) But for three hundred years, this application of glass remained a tool for seeing things up close. It was only during the burst of creativity around the year 1600 that a second wave of innovators like Galileo turned those glass lenses around and pointed them at new worlds, most famously the moons of Jupiter.

With paper, you could make the case that the story runs in reverse. For its first few centuries in Europe, paper was the tool that helped you see the big picture. With a cheap supply of paper notebooks, you could build complex financial models of your business with double-entry bookkeeping; you could design a cathedral dome with countless preparatory sketches. But paper would increasingly be used to augment our private thoughts and memories: the commonplace book, the diary, the personal correspondence, the first draft of a novel. These were tools that helped us see ourselves.

All of which left me thinking that if I were to add a new chapter or episode to How We Got To Now, it would have to be about paper. Like all the other innovations profiled in HWGTN, paper's influence is now so pervasive we barely notice it. But it triggered multitudes of unsung secondary effects, thanks to the diarists and the accountants. No one can reasonably contest the idea that the printed page was one of the most powerful engines of change the world has ever seen. But I suspect we've been underselling the transformative power of the blank page.

Thanks so much for this discussion of the book! I'm glad that you found so much of interest in it.

FWIW I really regret that I couldn't cover Islamic notebooks in more detail. I did try, at the beginning of my research, but got nowhere, and had to move on. Two years later, when I'd got much better at the research, I wanted to go back to it, but had no time left. Such is life. I would love to read a good account of Islamic / Ottoman equivalents to Zibaldoni, common-place books and so on.

Interesting point you make about the Italian merchant classes 'owning' the techniques of double entry collectively. They didn't really do Intellectual Property in those days... very few people were able to protect their ideas and monetise them exclusively. (Interestingly, Pacioli was one: he got a very early, exceptional, (c) protection for the Summa.

Nice piece, SBJ!