Writing At The Speed Of Thought

Will language models deepen our understanding of the world, or simply let us bypass the hard work of thinking for ourselves?

NotebookLM, the AI-powered tool for thought I've been building with Google Labs for the past year or so, officially launched to users in the U.S. on Friday. If you were in our early access program using NotebookLM earlier this summer, I highly recommend that you check it out again. The early access version was mostly our attempt to learn as much as possible about source-grounded AI. In other words, it was more of an experimental feature, not a product. The version that launched on Friday gives you a genuinely new interface for working in collaboration with a language model, creating a single, integrated space for reading, thinking, asking questions, and writing. Some of the most exciting features—what we call "suggested actions"—are going to be rolling out over the next week or two. But the main architecture is in place—and NotebookLM is now using Gemini Pro, Google's new AI model.

In his PlainText column at Wired on Friday, "Google’s NotebookLM Aims to Be the Ultimate Writing Assistant," Steven Levy tells the story of my long fascination with tools for thought, starting with my early obsession with Hypercard in the late 80s, some of which will be familiar to Adjacent Possible readers. (Amazingly, he quotes his own column from Macworld magazine in 1988 reviewing Hypercard, which I'm pretty sure is how I originally heard about the software when I was a sophomore in college—there basically wasn't any other way back then to keep up with Mac-related news.) He then describes his experience using NotebookLM, which provokes some very interesting thoughts on what a creative partnership with an AI is going to look like as these tools become more common:

The most annoying part of the writing process for me has always been constantly having to leave my manuscript to find the exact information I need in a transcript or document that I want to refer to or quote from. In writing this essay, when I wanted to remind myself of Johnson’s official title, NotebookLM instantly supplied the answer when I requested it. But that’s only one of its more prosaic uses. Deeper functions come in the form of analysis it can provide about your source material—not just the facts but the overall picture they paint. Right after you enter the sources, NotebookLM seems to arrive at its own opinions of what’s important about the topic and can suggest questions for you to ask it and themes to explore...

But here’s my worry. Users of NotebookLM, who simply want to get a good job done quickly might not take the time to do that hard work of thinking. They might not even bother to pore through the research materials themselves. Why take the time when your AI buddy has gone through the material much more closely than you and has already reached some nifty conclusions about it? Johnson doesn’t seem as worried about this as I am. First of all, he notes that users are under no obligation to engage in conceptual discourse with the app: They can happily use it for things like finding that passage where someone’s title is identified and things like that. But he clearly feels it’s a tremendous advantage to engage in such dialog. He’s thrilled that NotebookLM offers suggestions for themes to pursue. And you can even use a mode where NotebookLM can critique your work and argue the opposite side. “If I'm genuinely interested in getting to a unique take, NotebookLM should be able to help me get to that with less hassle,” he says, “and maybe even get to a more interesting take.”

I think there's a more general way of phrasing that last point of mine, beyond the journalistic framing of getting to an interesting "take." If you want to create the illusion of understanding something, you can indeed ask NotebookLM a question with the right sources and just copy and paste the answer, and make it look like you understand the topic at hand. (It's a little like John Searle's famous "Chinese room" thought experiment.) If you want to bluff your way through your work like that, creating little Potemkin Villages of fake understanding, language models will help you do it. And they're getting accurate enough—particularly with source-grounding—that the bluff will probably work for a while. But eventually you're going to hit a wall where someone actually asks you in real-time about the thing you allegedly understand, or you’ll have to perform a task that demands real understanding, and the whole charade will fall apart.

But my belief is that most people will use NotebookLM in a good-faith attempt to understand the material they're working with. And if you go into it with that underlying objective, the software is really quite remarkable. To give you just two examples: two of our upcoming "suggested actions" are "help me understand" and "critique." You can read a challenging passage in one of your sources, and just select the paragraph that's confusing you, and NotebookLM will automatically offer to help you understand it, translating the language into simpler terms or walking you through the logic of the passage so you can get your bearings. Or, as Steven Levy mentions in his piece, you can write a few paragraphs in a note, and then select those passages and ask NotebookLM to critique what you've just written.

For a taste of how that works in practice, I’ve selected the two paragraphs I just wrote and asked NotebookLM to critique them. This is what I got back:

Style:

• Avoid colloquial language: Replace phrases like "get to a unique take" and "bluff your way through" with more formal language. For example, "formulate an original perspective" and "simulate understanding without genuine comprehension."

• Use active voice: The text frequently uses passive voice, which can make sentences wordy and less engaging. For instance, instead of "the illusion of understanding can be created," write "one can create the illusion of understanding." *

• Vary sentence structure: The text contains several long and complex sentences. Break these up into shorter, more concise sentences to improve readability.

Argument:

• Strengthen the thesis statement: The opening sentence lacks a clear and concise thesis statement. Consider rephrasing it to explicitly state the main argument, such as: "While NotebookLM can facilitate the exploration of unique perspectives, it also poses potential risks by enabling the illusion of understanding."

• Provide evidence and examples: The argument often relies on assertions without sufficient supporting evidence. For example, the claim that NotebookLM can help users "get to a more interesting take" needs further elaboration and examples.

• Address counterarguments: The text acknowledges the potential for misuse of NotebookLM but does not adequately address counterarguments. Consider discussing how NotebookLM can be used ethically and responsibly to mitigate these risks.

I'll take up NotebookLM's provocation that I should give more detailed examples of how the software can stimulate deeper thinking and creativity. There are a lot of obvious ways the tool can do this. For instance, another suggested action that's about to roll out is "suggest related ideas": write a paragraph, select it, and NotebookLM will automatically surface facts or concepts from your sources that are relevant to what you've just written. Our “suggested questions” feature, which I wrote about in an earlier Adjacent Possible post, can also stimulate deeper understanding of your source material.

But there's another critical way that NotebookLM helps you "do your best thinking"—our tag line for the product—and that's as much about the interface as it is about the AI. The whole experience is designed to keep you in the writing/reading/thinking flow state, instead of constantly distracting you by forcing you to switch between tabs or applications. Steven Levy alludes to this when he talks about "the most annoying part of the writing process" where he has to leave his manuscript to go hunt for some information. This is not just a problem writers have. Anytime you've found yourself working on a project with ten tabs open, copying and pasting information between apps, trying to find the thing you're looking for with exact keyword matches using command-F—all that mode switching is just disastrous for your focus. It has a huge cognitive load. And it takes up valuable time—time that could be much better spent thinking or creating.

Here's a little test I conceived to give you a sense of what I mean. As many of you know, I have an archive of quotations that I've accumulated using tools like ReadWise over the past twenty years or so. It's 1.3 million words of quotes that I currently have spread out over fifteen separate documents. I also have those fifteen documents loaded as sources in a single notebook in NotebookLM. (Appropriately enough I called the notebook "Commonplace Book.") So the test is: how long will it take to find two quotes from two specific authors on specific topics and generate an idea for an interesting connection between the two quotes.

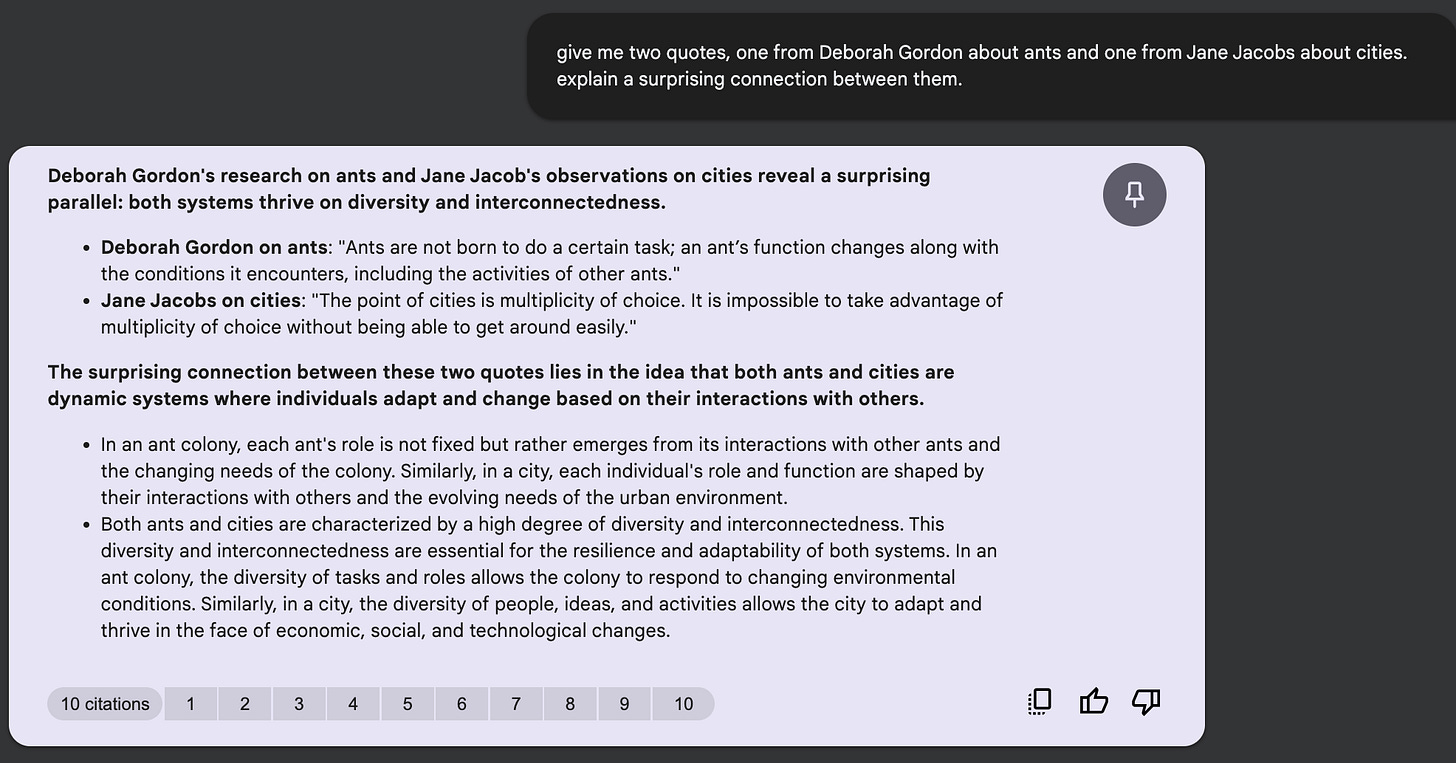

As a shout-out to some of the ideas in my second book, Emergence, I came up with this challenge: "give me two quotes: one about cities from Jane Jacobs and another about ant colonies from Deborah Gordon. explain a surprising connection between them."

If you do it the old-fashioned way, using Spotlight on the Mac or Drive search, it goes something like this: type in a query like "Jacobs Gordon ant colonies" and that will bring up a list of suggested documents that might be a match. Then you open those one by one, but at that point you have to command-F with exact key strings: "ant colonies" maybe, or "Gordon." You go through a bunch of documents and eventually you find one of the quotes. You copy it, switch tabs to Bard or ChatGPT, and paste it in, and then go back to searching by hand through your documents, looking for the second quote. Once you find that one, you paste it into the chatbot prompt window with the first quote, and add a line in the prompt requesting a short essay connecting the ideas in the two quotes.

That's what it takes to execute that particular task the old way. I ran the test myself and it took 5 minutes and 8 seconds of genuinely annoying work.

But in my Commonplace Book notebook, I just type the challenge instructions into the chat window and I get this.

That took 11 seconds to generate, or 20 seconds if you include the time spent typing the instructions. In other words, at least 15 times faster than a traditional multi-tab search-and-copy-paste adventure. The quotes are accurate; I can jump directly from the citations at the bottom to see them in their original context; the connection it draws between them is maybe a little on the general side, but not far at all from the argument that I made in Emergence. So now I have almost five additional minutes that I wouldn't have had before, to ask followup questions, or turn NotebookLM's initial summary into a more interesting “take”, or get help understanding the concepts.

That's what I hope you'll keep in mind if you get a chance to use NotebookLM: it's not just the new capabilities of a source-grounded language model; it's also the way the whole environment is designed to liberate you from the kind of mindless archival tasks that have always been a part of multi-document projects. It's designed to let you work at the speed of thought, with as few distractions as possible. If it succeeds, it should be a significant net positive for thinking and understanding, letting you go deeper and learn faster.

Since many of you share my obsession with tools for thought, I'm particularly interested in hearing what's working (and what's not) with NotebookLM for this community. You can share your experiences in the comments here, or send me an email at sbeej68@gmail.com. We also have a very active Discord community for NotebookLM if you'd like to join the conversation there.

This is fascinating and I do hope it continues to develop as a support for writers and that writers use it within these guidelines. I think we bump up against larger cultural conflicts that certainly aren’t the fault of the tool, but it highlights these issues. For example, a college professor friend has seen an alarming increase in her composition course of students doing what you advised against: copying and pasting without applying any thinking or analysis. I am sympathetic to students who have been taught that a good grade is the desired result, rather than learning to think. Mistakes are so much more instructive, but we never seem to allow anyone to make them. Here’s hoping that the increase in AI tools makes human elements in writing more valuable overall. Ok,

I feel like an old granny, even though the prospect of quoting sources at lightning speed is genuinely delicious. I will give this a test drive for sure.

Steven... I have just found this product and have used it for the last 3-4 days and find it really useful. I have a notebook with 4 long pdf documents related to Biblical prophecy and it is really surprising to see a concise summary of each document just by clicking on that document. Two great features I have already found; each question shows the number of citations and you can clickeach and review the actual citation, and the second is the suggested questions from the documents. A really beneficial way to study the material.

I'm not totally sure this is correct but it appears that when asking questions the results only come from the sources in the notebook which limits a bit continual investigation outside the notebook sources. For my needs it would be beneficial to have a ChatGPT like interface to the broader band of knowledge of the large lanugage models of the recent AI vintage.

I really think Google is onto something here and combined with broad LLM results could be spectacular.