The Books That Defined My 2021

Killer asteroids, zombie viruses, rogue machine learning algorithms, and the catastrophe of the agricultural revolution. In other words, it's time for some fun holiday gift suggestions!

[A quick housekeeping note: At the end of last week, I sent out the latest installment in my series on designing a workflow for thinking, this one all about one of the great and profoundly nerdy obsessions of my adult life: figuring out a productive system for managing the thousands of quotations I’ve assembled over the years from all my various research projects. That post only went out to paying subscribers, but anyone can read the overview of the series.]

Given the time of year, I thought it might be appropriate to do my version of a holiday gift guide, and mention some of the books that I found particularly engaging this year. These are not necessarily the best books I read in 2021, and many of them didn’t actually get published in 2021, but they are the books that I spent the most time thinking about over the past year.

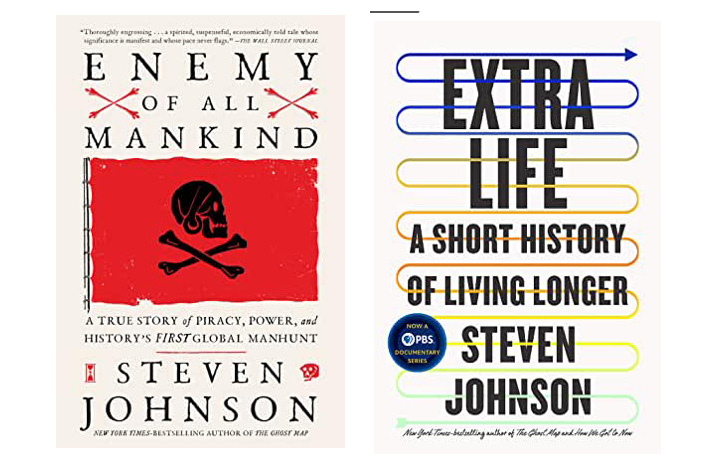

But before I get to the list, let me begin with a little self-promotion. If you’re looking for gifts to buy your history-minded friend or family member, I’d recommend my last two books. First, there’s Extra Life, which tells the heroic story of how we doubled life expectancy over the past hundred years. Admittedly I am biased about the quality and relevance of this book, but I will mention that some guy on Twitter named Barack Obama wrote that my writing on life expectancy “offers a useful reminder of the role of modern science in fundamentally transforming all of our lives.” So if you don’t won’t to take my word for it, you should listen to him.

The other book of mine that makes a thoughtful gift for the history buff in your extended clan is my 2020 book, Enemy of All Mankind, a true story about the pirate Henry Every, whose attack on an Indian treasure ship at the end of the 17th-century triggered a major crisis in the emerging multinational economy, and eventually led to the first global manhunt in history. (And a sensational trial back in London.) I think Enemy is my favorite of all the books I’ve written—it’s a thriller that’s interwoven with a dozen different historical threads about the birth of capitalism, the strangely progressive politics of pirate culture, the early tabloid media, and more.

Some of you may have seen that there’s a special tier of subscribers for this newsletter that I called “ideal readers.” The main perk of being an ideal reader is that for a few extra bucks a month you get a signed copy of each of my new books, starting with Extra Life. It occurred to me today that some of you might like to take advantage of the ideal reader subscription for your holiday shopping, and have me dedicate a copy of one of my books to someone as a gift. I’m happy to do that with either Extra Life or Enemy; just sign up for the Ideal Reader subscription and reply to this email with your address and the name of the recipient (and which book you’d like.)

If folks are interested in getting multiple copies, drop me a line and we can figure something out. It’s a little bit of a hassle on my end to get these off to the post office, but COVID took away so much of the ritual of in-person bookstore signings that part of me has really been enjoying getting to personalize books for people this past month since Adjacent Possible launched.

Okay, now onto the books not written by me…

Black and British: A Forgotten History by David Olusoga.

I’m kind of cheating at the very outset here, because technically I read this book several years ago, but I’m including it because it will forever be associated with 2021 thanks to my collaboration with David Olusoga on our PBS/BBC series Extra Life. I told David when I first read his book that it reminded me of Edward Said’s Orientalism—it’s a book that completely reverses so many of your assumptions about history, powerfully written throughout. Fantastic stories abound as well, including the life of the Jamaican-born Francis Barber, manservant to Samuel Johnson who ultimately made Barber his residual heir. It’s also an interesting book to read alongside The 1619 Project.

Against The Grain: A Deep History Of The Earliest States by James C. Scott.

I’m just about to start reading Graeber and Wengrow’s The Dawn of Everything—maybe the most talked-about book of the past few months—but reading some of the early reviews suggested to me that it has a lot of overlap with this astonishing book by James Scott, who is probably best known for his anarchist-themed history, Seeing Like A State. (Which was a central text for my book Future Perfect, written ten years ago.) Against the Grain wrestles with one of the great mysteries of human history, which is why our ancestors opted for the massive downgrade in health, diet, and lifestyle that the agriculture revolution offered. Scott makes a convincing case that, in fact, we have overstated how many humans did in fact make that choice—most provocatively that there were thousands of years dominated by a kind of mixed-use model where people dabbled in agriculture but never developed oppressive state institutions.

Life’s Edge: The Search For What It Means to Be Alive by Carl Zimmer.

On one of the many long email threads with old friends that flourished during COVID, we somehow got onto the question of how to define life itself, perhaps because we were living in an age where the world had been radically upturned by an virus that was itself halfway between a living and non-living thing. That led me to pick up this new book from one of the great science writers of our time, Carl Zimmer, and it did not disappoint. It’s a history of a question—what does it mean for something to be alive—but the ultimate point is really that the answer to that question remains shockingly blurry.

The Alignment Problem: Machine Learning and Human Values by Brian Christian

I just finished this book a few weeks ago and it is still reverberating in my mind, which is probably appropriate since it is on some level a book about how we think and how we learn, seen through the lens of the latest developments in machine learning and AI. If you read Nick Bostrom’s Superintelligence, you will already be aware of the general framing: how do we build artificial intelligence that is fundamentally aligned with human values? But Christian’s book provides a much more concrete set of potential answers to that question, takes you through the extraordinary history of how researchers clawed their way out of the “AI winter” to get us to the place we are today, where machine learning algorithms are finally starting to deliver on their promise.

The Bomber Mafia: A Dream, a Temptation, and the Longest Night of the Second World War by Malcolm Gladwell

I put this on the list not so much because of the content of the book—which, given that it is Malcolm Gladwell writing it, is very entertaining and to some critics maddening—but rather because of the form. It’s one of the first truly audio-first books that I’ve encountered, both in the prose style which has clearly been written from the ground up to be heard, not read, and in the elaborate sound design of the whole experience, so different from a traditional audiobook where it’s just you and the author’s voice. I think this is a fantastic new genre, and one that I plan to experiment with myself in 2022.

The Precipice: Existential Risk and the Future of Humanity by Toby Ord.

I’m working on a new project that touches on the question of existential risk, and so I found my way to this book by Toby Ord, who got so obsessed with the urgency of existential risk as a field of study that he basically dropped all the pioneering work he had done co-founding the “effective altruism” movement to focus exclusively on all the ways that we might destroy ourselves. I wouldn’t say that this is the most compelling book I’ve ever read in terms of the prose style or storytelling, but it does provide a very helpful, almost quantitative overview of all the potential threats looming out there, along with some suggested tactics for humans to avoid them.

I finally got around to reading Susan Choi’s National Book Award-winning novel from a few years ago this summer, and in part because I spent a lot of my high school years in a “theater kid” environment very similar to the setting of Trust Exercise, I found it immediately recognizable. But what really makes it brilliant is a kind of meta-fictional twist that happens in the middle of the book, which—like the ending of McEwan’s Atonement—has the strange effect of making the whole narrative seem oddly more realistic, even as it is exposing the underlying mechanisms of the narrative itself. (Jean Hanff Korelitz’s The Plot also does something similar, though in more of a beach-read thriller mode.)

That’s my list — I hope there’s something useful for some of you as you begin your holiday shopping. And do let me know if you’d like to have a signed copy of one of mine to give to someone this season…

Steven